Lucinda McCray's research into the social history of medicine began in the 1970s, back when the field was new and relatively under-explored. Since then, she's worked as a historian at Illinois State University and Appalachian State University and penned a number of papers and books on public health histories in both the U.K. and the U.S., including "A Matter of Life and Death: Health, Medicine and Illness in McLean County 1830-1995" and "Health Culture in the Heartland: 1880-1980."

With such a background, McCray is confident in saying that recent displays or protestations against COVID-related public health measures are not new territory; the ground has already been trodden via previous public health crises and subsequent responses in history — although, today, there is at least one new aspect informing some waves of anti-public health sentiments.

"What we have today that was not as true in the past is this 'whipping up' of resistance to public health based on the political goals of political groups that, really, have comparatively little to do with the public health question at hand," she said in a recent interview with WGLT. "That has an awful lot to do with this antigovernment feeling that's been whipped up since the 1980s."

"We seem to be fully capable of repeating the mistakes of the past over and over again and this really disheartening."Lucina McCray, author and historian

Public health and related measures, even in McLean County, McCray said, have always been things that are "highly political — and they were highly expensive."

Take, for example, the establishment of a public sewer system around the 1870s in McLean County — around the same time McCray dates an organized public health system as beginning to take form locally. Although that work started in the 1870s as a public health measure, McCray said it took until the 1920s to construct a necessary, complementary measure — a sewage treatment plant — and even then, the matter was "forced by a lawsuit."

"The farmers who were taking the river of sewage that was coming out of Sugar Creek were complaining that their farms were so polluted, their kids were sick and their livestock was deformed, and this was because they were getting Bloomington-Normal sewage," she said. But "even after you get the community forced to treat its sewage, there is still the problem of hooking up houses that had been dependent on outhouses since they were built in the 19th century.

"This had to be done at the householders' own cost, so householders very often chose to continue to depend on outhouses that routinely brought typhoid fever into the community."

Prior to an organized public health establishment in McLean County, it wasn't uncommon for some municipal leaders to take matters into their own hands. In "A Matter of Life and Death," McCray notes that passengers on some trains heading into Bloomington were, in some cases, not permitted to disembark since they came from areas with outbreaks of contagious illness.

Looking at that example might tempt one to think that public health systems of the past were previously more aggressive toward contagious disease than now, but McCray notes these kind of efforts, while not uncommon across the country were "ad hoc," likely decided by individual municipal leaders, versus public health departments, and it's unclear "how effective" they were.

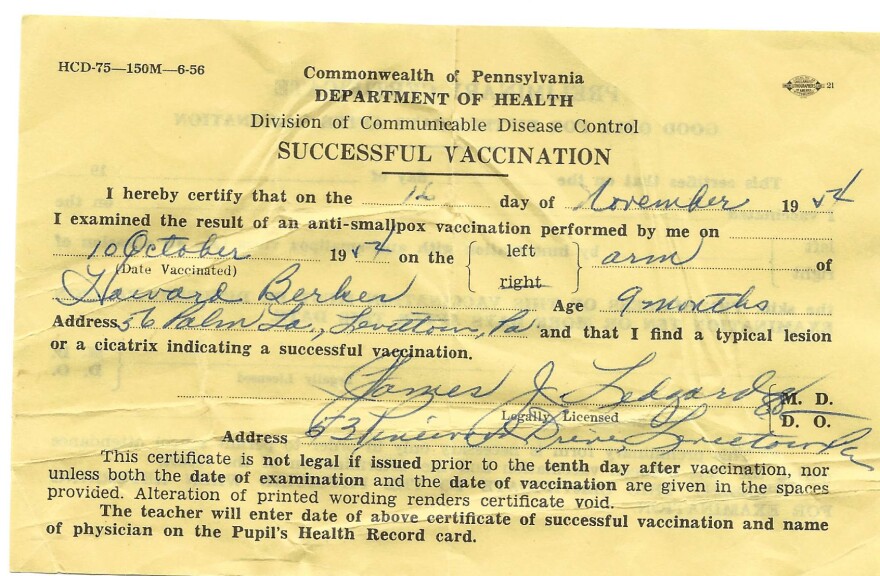

And while some may wish to point to previous waves of mass vaccination efforts as being more successful or widespread than the current COVID-19 vaccination movement, antivaccination sentiments arose even then.

Organized public health administrations in 1850s Great Britain — another of McCray's areas of study — began enforcing laws that required people to get vaccinated against deadly smallpox. And while those departments were "a lot stronger, more thoroughly staffed and more completely organized" than their U.S. counterparts, there still rose a "significant antivaccination movement."

"The basis of objection to vaccination, in that movement, was both government and social class overreach: People object to the fact that, unfortunately, smallpox vaccinations were administered by the old workhouse," she said. "They thought it stigmatized 'respectable,' working-class people to be forced to go to the workhouse to get vaccinated. So, it's not as simple of a question to (posit) that, in the past, people were more community-minded than they are now."

All of that noted, however, McCray said watching the COVID-19 pandemic, along with responses to it, has shown her a new aspect of history.

"I never realized until fairly recently just how political history itself is. I guess it's part of the reason that every generation needs to write its own history and should write its own history," she said. "But that is also a reason that need to keep observing the past: It remains with us. I guess my plea, as a lifelong, professional historian, is that we need to do that wisely and learn from it. We seem to be fully capable of repeating the mistakes of the past over and over again and this really disheartening."