Brandon Lusala's parents immigrated to the United States from what was then the Congo for work. His father worked for State Farm in Bloomington, his mother was a nurse. He attended Northpoint Elementary School, Kingsley Junior High and Normal Community High School.

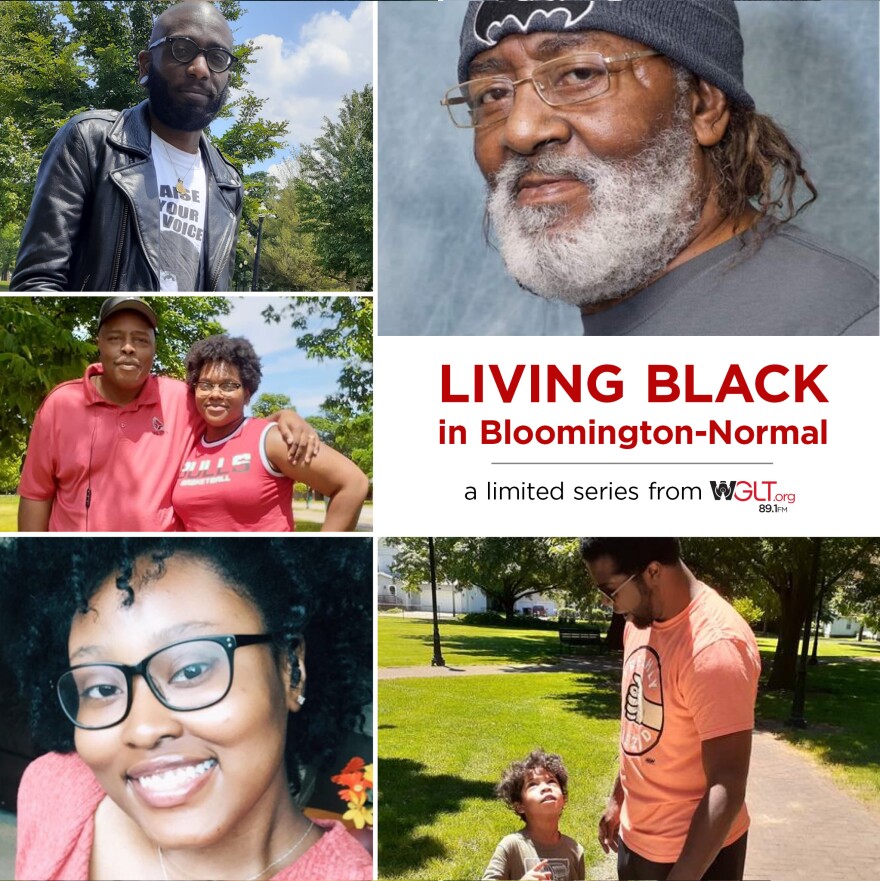

He currently lives in suburban Atlanta, Georgia, where he works in Internet auto sales. Lusala spoke with Jon Norton for the WGLT series Living Black in Bloomington-Normal. Contact us if you'd like to be featured in the series.

As a first generation African American, how do you feel your experience dealing with race has been or was different than other Black people?

Really, my experience was different because not only did I have to deal with people looking at me differently because I'm Black, but I had to deal with people looking at me differently because I'm African American. And my parents are from the Congo. That really happened with white people, Black people, people all across the board.

For example, when I was very young, my mother had a job at the hospital there. And one of my first experiences with racism was she came home and told a story about a gentleman who would point to the pictures on a National Geographic magazine and say, “Oh, that's where,” I don't want to use her name, but that's where my mother's from, that's her family. And I remember getting extremely angry and realizing not everyone is going to like me, for me, I'm not going to get the opportunity to be judged based off of my personality. There are some people who are going to look at me and instantly dislike me for the color of my skin, who my family is, so on and so forth.

How did your mother react? Do you remember?

I remember she was upset. She told my father about it. And between the two of them … my mother's … I take after her, she's very emotional. So, when something happens, she's wanting to get upset and my father's very … you know … let's formulate a plan. So she came home, she told all of us about it. She talked with my father about it, and that was something where she went back to work and addressed it with her higher-ups.

How did that go?

It was something where that gentleman was pulled into a private conversation and reprimanded and instead of apologizing, it was something where he never acknowledged my mother from that period of time on.

What message does that convey to your mother and ultimately, to you, and probably your father, when someone says something like that?

That message that we all took from it personally is that they're still … people will look at us and say, “Oh, these are African American individuals who are from Africa” and still try and put us into that stereotype of how society thinks of people from Africa, you know, for a long time until recently, there was this rather negative perception of people from Africa that were just like your stereotypical indigenous people with spears and don't speak English and things like that. It was like we were put into that box. Really, of … this is who you are.

Did your parents talk about how they did adapt to living in the United States?

As I got older, I spent a lot of time with my dad. So, there was a lot of time where he and I would talk and he would say, like, “Understand who you are, but still form your own path. Be your own person. Don't be defined by who I am, where you come from. Still be proud of that, but still be able to formulate your own path.” For example, as I got older and into high school, he said, “There's a lot of people who are gonna judge you because you're African American, and they're gonna say things just get a rise out of you.”

I went to high school around the time where comedians like Dave Chappelle got popular, so a lot of his jokes are racially motivated. So, people would see his material and repeat his material. And people would repeat his material to me. And they do it thinking it was funny. And that's one thing my father addressed with me. He said, “When you see stuff like that, don't take it as humor. Understand that that's not OK.” That's not something you can just walk up and say to somebody like, it's not OK for someone to go, Hey, Brandon, you're the token Black guy. Like that's not. That's not funny.

There is research out there that shows African American immigrants tend to think Blacks are too quick to label something racist. Native Blacks respond that immigrants haven't fully experienced what they have so they can't really quite understand where that comes from. Did that dynamic play out in your house at all?

Yes, because sometimes, I've had conversations with my father. And I've told him things that I've gone through and he said, “Hey, I don't see how that's a skin color thing. I don't see how that's something I'm aware of that's racist, or you're being attacked because you're a Black man.” And then he'll always stop and say, “Well, we all have different experiences, so I may see one thing a different way, and you may see it another way.” And I think a lot of it is that as native Blacks and Africans, we experience two different spectrums is really what I've been trying to get out. You know, we experience as Africans, we're experiencing things like being looked at differently because we're from Africa, trying to break out of that stereotypical mold, versus when native African Americans are viewed differently because of trying to break out of the mold of how people view Native Blacks.

You talked about that experience with your mother in the hospital, how your father reacted to it. And you talked about your friends repeating Dave Chappelle jokes. Can you talk about other experiences that happened to you? Maybe a number of things that might have happened that shaped how you view this whole thing?

Oh, yes.

So, in school, one thing I've noticed that would happen to me a lot, is I'd get told “you're not Black,” “you're an Oreo,” things to that regard. And a lot of it would come from the fact that I don't fit into the stereotype of what you think a Black kid should be in the time where I went to school. I was well educated, I listened to a lot of different kinds of music. So, I'd have all sorts of people saying, “Oh, Brandon, he's not Black.” I remember, there was one issue where I got an argument with someone at school. I remember the guy vividly, he walked up to me and he said, “Brandon, I'm Blacker than you.” And I remember I got extremely angry. And it all started over a pair of nice jeans that my dad had gotten me for my birthday that I had on. He said, “I'm Blacker than you.” And I remember telling him, “How can you say that to me when I was born this way, this isn't something I can go and take off, you know, this is who I am. Why do you try to make the color of my skin into a trend?” That is what I had to deal with personally growing up in Bloomington. People viewing being Black as a trend when these things happen.

Did you feel your school administration at the time was receptive to these … I'll call them microaggressions … are going on … they need to be dealt with?

Honestly, I've had a lot of those issues in school. I had someone call me the N-word. And I remember I brought it to the principal. And I told him about it. And I remember that student received like a small detention. And I remember being told by the principal that he felt that the African American teacher who overheard the incident handled it pretty well. And I remember being upset because I felt like that student just got a slap on the wrist. And that's something that that entire school system I went through, I felt like they would just give out slaps on the wrist, it would never be some serious justification with that … there would never be an attempt to try and correct the issue. Like, get down to the root of it.

How do you live with that? What does that do to your psyche?

With me, when that student called me a racial slur and I brought it to the school, they handled it the way they did. I remember I went home and I was angry about it for a few days. And after a while, I took their approach. If the school's not gonna handle it, then (A) I have to be willing to defend myself and stand up for myself when these issues happen. And (B), I have to realize that now when certain things happen, there are certain people who I can't go to looking for help. Say, another issue happened after that, I realized certain things. I can't just say, “Oh, I'm going to go to the principal or a teacher about it,” because they're just going to do the same thing and it's going to be the same result.

Other than dealing with it yourself, did you feel you had anyone else you could go to about that?

Yeah, I know I had my parents. But at the same time with my parents, I knew there were sometimes where if I took it to my dad, there wasn't always going to be a time where I would be angry … and I'd be thinking, “OK, I want somebody to go in there and shake the system and really get things going.” So, I know if I took it to my dad, he wasn't … he's not the type of person to do that. So, a lot of times with him when I take it to him, he does tell me, “You know, avoid that person and let it go.” So, yes, I had people who I know I can come to but at the same time, I knew I had to adjust how I came to those people if that makes sense.

You mentioned your father and your mother certainly had a different temperament. What did you take from both of them?

From my mother, I took “never take anything from anybody.” Always be willing to stand up for yourself. To this day she always tells me, you know, when something happens, you are your best advocate. When you want something, when you feel something needs to change, always be willing to stand up for yourself and be the change that you're wanting to see. So, with that, it's like, I can't sit here and say, all these negative things are going on in the world, but then in turn, not do my part to try and make the world a better place.

And with my father, I learned from him, there's a right … this may sound cliché … forgive me, but there's a right way and there's a wrong way to handle things. To view life like a chess game, always keep yourself two steps ahead of everybody else. So, when everyone else thinks you're going left, you've already made a right turn and another left turn, and you're in a position ahead of everybody else to where now you're better off than you ever could have imagined.

How did your parents talk with you when you were younger about how to conduct yourself around law enforcement and other white people? And do you feel it might have been different than other Black parents have with their children?

Really the thing my parents told me … and this mainly came from my father. Now I hear the two sides of it because I had a conversation with my father about it and then my mother. With my father, it was always respectful and be complicit. And with my mother, it was … when it came to dating … just avoid white women who are always going to get you in trouble. My mother thinks I can always avoid the situation. But my father, I think he has a perspective on … it's going to happen one way or another. And you have to prepare to get yourself out of that situation.

You grew up in Bloomington-Normal. You now live in suburban Atlanta, Georgia. Are there different differences from when you grew up here in Bloomington-Normal and where you now live?

Yes. Honestly, it’s night and day. It's night and day to see how people interact with each other here versus how people were interacting when I was growing up in Bloomington. In Bloomington, everything was kind of hush hush and like, people weren't open as open with their feelings. Now here in Georgia, I've noticed a lot of people, they're very open. They're very, they don't care what the other party thinks. They'll say what's on their mind.

It was hush hush in Bloomington like it, you wouldn't find a lot of people who would come out and say like, who would be open about the fact that, for example, with dating, open that they don't want their children dating a Black guy. It'd be something where if the child was involved with a Black man like I had that situation. They tell the child and the child will tell that person. Now here, it's something where you'll see a lot of people who are very open with their dislike. They'll say anything that comes to mind.

Like, at my job, I've had a lot of people who asked me a lot of questions publicly that really shouldn't be asked. Like, I just had a conversation with someone who asked me, “Brandon, what did African people think of slavery?” Like, did they think it was a good thing like a free trip to America? And of course, we all know what African American people think of slavery. It's night and day here.

That's a stunning question.

It really, really is. It floored me that that was something that was asked prominently, like I had another co-worker who flat out said, “Well, I like to be referred to as Black American. I don’t want to be called African. I'm not African. You're African.” And I explained and I said, “Well, I was born here. So, I'm just as American as you are.

And on the other hand, if you go deep enough in your family, you're going to find someone who's like me, the first generation born here. So, I've noticed here, (Atlanta) people are very quick to denounce African people as a whole. They're very quick to bad mouth and quick to they look at it like it's a negative.

I talked with a woman recently who said, what you're just describing all of this stuff you have to navigate and think about, it's like living life … plus. I have all the anxieties, I have all the stresses that any normal person has, plus I have systemic racism. I have all the worries about my kids, you know, getting good grades, plus, I've got to deal with comments like you just talked about. How would you describe what you have to deal with every day and what that adds to your life?

To use an analogy. It's like walking through a minefield. I have to always make my way throughout my day … like, for example, when I go to work, I have to think to myself, OK, they may say something, like I just told you, but I have to always know that if I respond the wrong way, it's going to blow up and it's going to create a major problem. So I'm always thinking to myself, remember, Brandon, be careful, somebody's going to say the wrong thing. You have to control how you react. Because that's all you can do at the end of the day.

I've asked a lot of questions from my perspective. And you certainly wanted to talk about being a first-generation African American and how that experience, you know, might be a little bit different than others have experienced here. Is there anything else you'd like to add? Or something that you feel I missed that you would like to get across?

Really, the main thing I just wanted to use this platform to say is … as an African American, you know, we're looked at a first-generation. When you see that close link between us and Africa, people look at that as a negative. And it's something where, for a long time, I felt like it was the divide amongst Black people in general. We've all seen the whole thing of light-skinned versus dark-skinned, long hair versus curly hair. But nobody wants to acknowledge that divide of like, they're still Native American Black people who look down at Africans in general. And that's one thing I wanted to acknowledge and make sure I vocalize.

Can you expand on that a little bit?

Sure.

You know, with what I've said throughout this interview, I've given a lot of examples of it, and it's something that it's prevalent, like in school, even something finding out their names. You know, like, I had people who made fun of me for my last name being Lusala. What is that? Where are you from? People used to call me Kunta Kinte in school, the character from "Roots." You know, I had a lot of people who would laugh at that, and still try to make me view that as a negative and kind of not be proud of who I am. And I think that's something that within the current times needs to be addressed. Not only is there that issue amongst racism in general, but there's the issue of how as Black people we treat each other. And that's something that I want, I hope, and I pray is addressed in this current time and current climate.

WGLT depends on financial support from users to bring you stories and interviews like this one. As someone who values experienced, knowledgeable, and award-winning journalists covering meaningful stories in central Illinois, please consider making a contribution.