Christie Vellella is a Chicago native who came to Illinois State University in the 70s. She is a retired teacher and social worker in Bloomington-Normal.

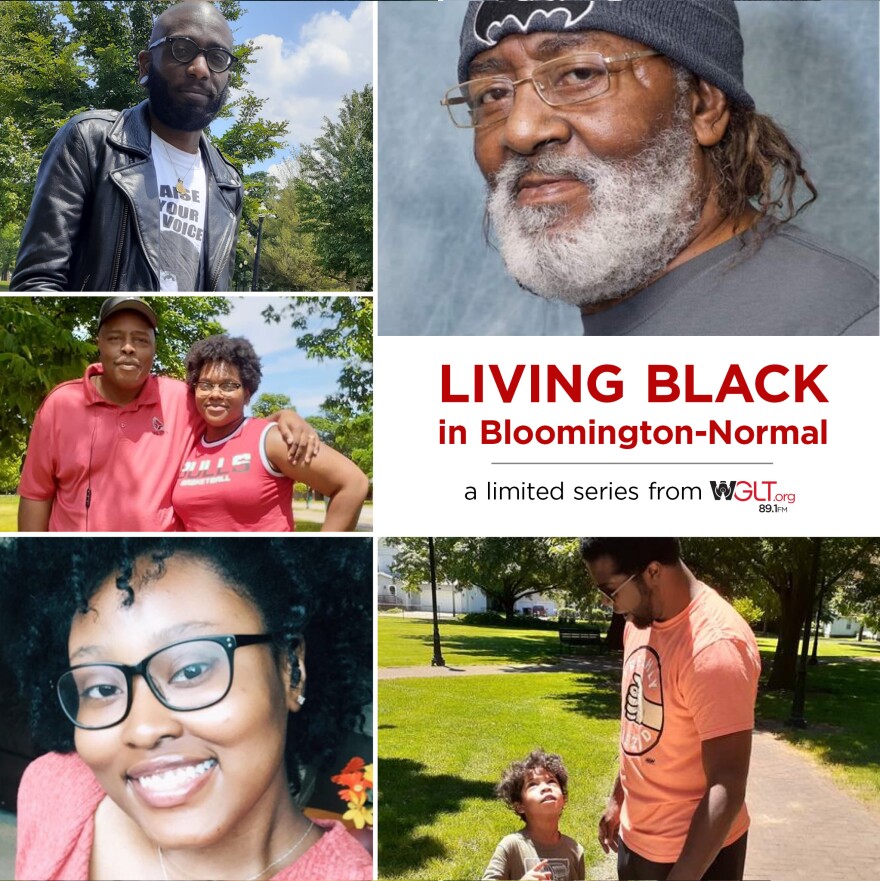

She spoke with Ariele Jones for the WGLT series Living Black in Bloomington-Normal. Contact us if you'd like to be featured in the series.

How do you feel systemic racism has affected you in your life?

Racism has a lot of different faces, and I have spent a lot of years on this earth. I was alive during the 60s. I was shielded from a lot of what was going on with the civil rights movement, but I did know some of it. And so, at that point, people were kind of picking a side. African Americans were picking a side basically, Martin Luther King side or a Malcolm X side, which, you know, kind of goes with their methodology as far as by any means necessary or nonviolent Christian background-type things. So it was a ... it was a very complicated time. We tended toward the Christian, Martin Luther King-type approach to civil rights.

We got up every morning and listened to the Rev. Jesse Jackson on Operation Push. That was what we did while we were doing our chores. We listened to the radio while he had everybody repeat, "I am somebody. I may be black, but I am somebody, I may be poor," etc, etc. So those were the things that were going as far as awareness of race. But you do have to understand that Chicago is a very, very segregated city, not just black versus white. At least at that time. Polish people didn't live in a Lithuanian neighborhood, it was that segregated. And so, in my day-to-day life, there was not much racism as we know it, just because my teachers were Black. My doctor was Black, the grocer. There was an occasional Caucasian person in my south side, Chicago neighborhood, but they were mostly people we knew so you didn't really consider them white or you didn't really think about their race, because that was Mrs. So and So.

You're talking about the south side of Chicago in the 60s and 70s, and we're in 2020 right now. How are the times now affecting you? Do you feel like it's repeating?

There's some real deja vu going on with some of the things, with the George Floyd incident and similar incidents, and there are a lot of less dramatic things that have gone on over time. The microaggressions are what I have come in contact with most, in last several years as opposed to any blatant racism.

Do you feel that's a Bloomington-Normal thing or being Black in Bloomington-Normal thing? Slash, maybe being a person of color in Bloomington with the microaggressions?

Yes, yes. And the microaggressions that I've been, I've been fortunate enough to be in a professional arena for most of that time. So at the university and then in the school system, so I was mostly among professionals who wouldn't, drop the N-word at me, for example, but colleagues who would come to me as the only African American in the building and say, "Well, how do you pronounce this name of this student?"

I said, "Well, I've never seen that name before, so I don't know anything more about that name than you do," but so there are assumptions made sometimes and completely not ill intended. Here's a teacher wanting to make their student feel more comfortable by pronouncing their name correctly, but yet assuming that because I'm African American, I would know. And the typical microaggressions that African Americans, particularly in the educational arena, or professional places, just come into contact with people who will say, "Oh, well, you're not like the rest of them. You are able to speak Standard English, you don't speak like the rest of them," and having to patiently explain that there is no rest of them. I don't assume that you are just like a Caucasian person that lives next door to you.

But I do have to say that there is a strange racism that I experience as well.

Tell me more about that.

The strange racism is actually an intra-race racism that I don't think a lot of Black people are aware of. Like my appearance, and particularly as a young person with light-colored hair, among African Americans there were the microaggressions, assumptions being made that I was not quite as Black because of my appearance. But then coming to Bloomington-Normal, now there is also kind of an assumption or people saying, well, you could pass for white, as though that's something I would want to do.

Like that's a plus for you.

Yes.

Gold star. You could pass.

Occasionally my mom would have somebody ask her, are you a mulatto? And I would just back up, like, oh, here we go with, my mother's explanation that a "mulatto" is a slave term. It's a slave classification, so why would you even say that? And then fast forward now, people wouldn't dream of asking me something like that, but I run into pockets. I run into people who call ... who refer to me as colored because in some families, let's say "colored" is less objectionable, they think, than Black. So I'm assuming that if they were at home, they probably say the N-word, but because they're in polite society, they're going say colored, maybe.

But if we're talking about right now, I have been really pleased with Bloomington-Normal's response to what's been going on. What's been going on, both at a community level and at a neighborhood and personal level. I thought, oh, here we come, we're going to see where people shake out. I'm going to find out things about my friends and neighbors, some of which might not be that comfortable. I'm going to hear something when my Black Lives Matter sign goes up in my yard. And yet what I've seen has been positive.

Because of being in Bloomington-Normal, and I go to a church, which is primarily Caucasian, because of my background as a Missouri Synod Lutheran, that started in my Black church in Chicago. So, those are the doctrines that I'm familiar with and believe in, so when I attend my church now, it's primarily a Caucasian congregation, but I've been so pleasantly surprised.

I go to Trinity Lutheran and you can edit that out if you're not supposed to name drop. Some great things happened shortly after George Floyd and after the protest. The youth director from my church called me and a few other African American members of our congregation and said, would you feel comfortable answering some questions or giving some information, because these junior high and high school students are wondering and—

Does that ever annoy you?

It does not.

...like being like a person, a point person, to talk about that, because of the color of your skin?

Because of who I've always been, which means it visually standing out like a sore thumb, it's such an ingrained thing to me to want to explain who I am. And so my position is, if there are things that you don't understand, ask me and and I will tell you plainly, I'm not a spokesman for all Black people. But I am one Black person and I can tell you, in which that's why it was great that they had a panel of African Americans who might have different perspectives. So yeah, I am one person. I might not be able to pronounce everybody's name, but I can tell you what I feel about that.

Things like explaining to high school students that Black Lives Matter doesn't mean no other lives matter. Nobody said that. That's a different conversation. We say Black Lives Matter because some people don't have the awareness that that's true. So I said, if you see Black Lives Matter, and you want to say in your head, Black Lives Matter, too, I'm good with that.

On a personal level, I put up ... Let's get together and have a little online prayer. I said, myself and my grandkids are going to go in my front yard, and we're going to pray at noon on this particular day.

I didn't know I would be joined. There was a couple from my church, and some friends, you know, friends from down the street. There were neighbors who sat, this is when social distancing was pretty new, they sat in their lawn, but looking, and we had just a prayer for unity and peace and all kinds of things and I was just really overwhelmed by the people who wanted to participate online. And the people who came in person, and these were mostly Caucasian people, and what's different right now, this is such a great opportunity, with social media, unity minded people of all races, have an opportunity. We can understand each other better, we can stop making harmful assumptions about each other, which I'm guilty too. I have my prejudices.

When I first put my sign up, there was an older lady...when I say older, she's probably my age, who came to my door rang my doorbell and I'm like, OK, here we go. And she said, "Could you tell me where I could get a sign like yours?" And that's not the only time that's happened.

Being in Bloomington-Normal typically means that all of your friends are not going to be African American. We don't have really a Black neighborhood. There are more Black people in certain parts of town, but there isn't a Black neighborhood. We're everywhere ... but at the same time, it feels more like this is what the world should be like.

There was an incident where the police in Bloomington responded to a complaint. The person complaining seemed to assume that the people harassing them about their Trump signs were their neighbors. Their neighbors are very active in the community, just wonderful people who had a car that was similar to the one that drove by. But they made that assumption that it was the African Americans who were yelling anti-Trump things and as they as the police got further into the case, as it turns out, the people occupying that car were not the people that they were looking for and yet this couple, salt of the earth people in our community, were basically harassed by an accusation being made.

A Caucasian friend and colleague that lives very close to that said, you know, I've always wanted us to have more diversity in our neighborhood and I want to say to my Black friends, "Oh this is a great neighborhood come live here," but she said after this, I'm not sure I can do that.

And I'm like, honey, like Black people know. They know that what happened on that street could happen to any of us, at any time. There's things that we know about, for example, when I go to buy a car, I usually send my husband first, who is State Farm employee and Caucasian. I will send him there first to start the wheeling and dealing process, because I know how that goes. Black people, and particularly black women, pay more for cars, we just do. Things like that, you know, to go in to get a bank loan or things like that, I would want to at least have my husband with me and that's a shame. But these are the things Black people face all the time. It's always under the surface.

You know, there's a good book called "Waking Up White" and it's about, a little bit about white privilege, but mostly about things that you don't think about. When I get up in the morning and go look in the mirror, one of my big things is, what am I gonna do with this hair or if you're new in the Bloomington community, who's gonna do my hair, who is available? I have to find somebody who can do my hair. I have to find where I can shop for my food that I like, my skin products.

There's a whole set of things that you encounter as a Black person in any neighborhood really.

I have to wonder, and I don't wonder about my own neighborhood, because my own block is full of some wonderful people. And you know if they don't like me, they're not saying. I've been treated very well by my neighbors, but when I moved to my block, newly, if I ran out of sugar, I was going to Osco. I was not going to knock on the neighbor's door first thing to borrow something.

Other things that I don't know if it's just me, or if it's everybody, but there are so many stereotypes about us, running around. I would tell my kids as they were growing up, if you want to fight with your siblings, do it in the house. If you look like a maniac because your clothes are too small or they're raggedy or whatever, you wear them in the backyard. You don't go out front like that. And people shouldn't have to consider themselves being judged constantly.

But there is that disclaimer that as a person of color, as Black person, there are things that you will encounter and how you present yourself is either going to further prove the stereotype or dispel the stereotype. That's so much work.

It's always under the surface. At least Black people, particularly Black professionals, but also my family. My children were raised to be bilingual as was I. My husband can tell, like, if I'm talking on the phone to my sister, I flip right into Ebonics. He already knows or one of my girlfriends he knows. Just like, I know, when he's talking to his friends in Wisconsin, you know, because that code switching, we both grown up with it, or we both gotten used to it and what's unfortunate about people who are in lower socio economic and educational subgroups, code switching is something that they don't learn well. And so when you are already African American, you have social and economic disadvantages. Getting your needs met when you don't know how to code switch can be infuriating. People are making judgments about you and you don't know what they are. And you don't know, is it what I'm wearing? Did I shower enough today? Is it my skin? Is it the way I speak?

But then I have that "strange racism" where I have to walk that line because there are people who consider me a sellout. There are people who, if I put something on Facebook about going to a play in Chicago, something as innocuous as that.

Now, it's all about choices. We have choices.

Do you feel like you can live fully free in Bloomington-Normal?

I do. There are people who have probably unfriended me. There are people who don't consider me with the in crowd, but one of the things wonderful things about getting old is that you can adopt that Dr. Seuss attitude of say what you mean, because the people who matter won't mind and the people who mind won't matter. So if there are people that have a difficulty with my choices, there are plenty of wonderful people who support me in my choices. And if I don't cherry pick by race, for who's going to be my friends, who's going to be in my inner circle, I have what I need.

Bloomington-Normal doesn't have a very big African American community, so if I were to want to find someone who is very much like me, those numbers would be very small. So I try to look at the people that I have that are my friends have common interests, like theater and education. I'm a volunteer counselor. So those are the commonalities that join me.

Now granted, my African American friends and I have shorthand, especially those from Chicago. There are things that we just don't have to explain. There's a certain shorthand of any people that share a background and in Bloomington-Normal for the most part, I have felt free to do that to be who I really am.

Based on what you've learned and what you've gone through, how have you been able to pass that down to your kids? How do you, what do you do as a mom? How do you infuse them with, they're going to be these roadblocks, especially in town, how do you tell them don't get stopped by those roadblocks; there's ways around it, under it, over it, someway somehow.

Their biological dad has been very instrumental in being involved in the struggle, as we say, and voicing those opinions of, this is what you need to watch out for. And my input to that is let's start it on family level. Inside these walls, this is us, we have each other. So outside of these walls is the first layer, Black, white, whatever, we learn who we can trust. That happened very well in Bloomington-Normal.

At the same time, my oldest son talks about having been the only Black kid at Trinity Lutheran School when he started there. And he said he was just waiting. He was just waiting for, for something bad to happen and at the school, it never came.

He was unusual because he's 40 years old now, so you want to think that long ago, he might have been the first African American kid, some of these kids had seen and yet there was never an atmosphere of threat or discrimination or anything that he ever felt and I you know, and I can confirm that with my experiences there, too.

All I can think about though, is I feel like that experience, no matter how well it panned out, to have that on your back, like I'm just waiting, I'm just waiting for something to happen. That's almost like the Black experience.

Here's what happened when something did happen, I didn't respond to it very well.

At Sunday School of all places, some kid who, by my appearance thought I was Caucasian, called my son a "twist cone," and I laughed, which was not an empathetic parent-type thing to do, but I had heard that one. Then my son got in trouble for hitting somebody.

But yeah, so you're always on that level. That being said, how do I take my Christian background and my Christian priorities as far as how to raise my kids, how do I make that work? Well, we had to seek outside places to find the culture. So for example, when my kids were going to Trinity Lutheran Church, as little kids, back in the day, Mount Pisgah, was right across the street. They would go to Sunday school at our church, and then we'd slip over to Mount Pisgah occasionally and have service there so they had the experience of that style of worship and get to know those African American peers and parents and things like that to learn some of those social norms that they wouldn't otherwise get.

There was also a group called Umoja long time ago that was about Black history. Also through dance and theatre they were exposed to a lot of African American culture.

However, they were also exposed to not discriminating as far as who we have in our hearts and in our lives. I have four grandchildren, they are all biracial. I have four children. I have four grandchildren, all of the children are biracial and this current generation, the grandchild who is old enough to say, she doesn't claim being one or the other.

She did a report for school. They did kind of a family tree. She traced her Caucasian mother's Irish and other background, other European background and our African American and Native American and I think her caption is my family looks like America.

And my daughter was married to a gentleman from India, so our holiday pictures look like a Benetton ad. We have everything and I think that really says where we are.

I'm very selfish and I am very opinionated as you see. I want Bloomington-Normal and America to be like my family, everybody's welcome. You can be who you are, as long as you lead with love. You can be who you are, and be welcome. You are equal in our eyes.

Is there anything else you want to say?

Those of us who saw this happen in the 60s and 70s, we saw what didn't work and we see what works, so we're going to vote, we're going to throw money and support behind what we believe is right.

We’re living in unprecedented times when information changes by the minute. WGLT will continue to be here for you, keeping you up-to-date with the live, local and trusted news you need. Help ensure WGLT can continue with its in-depth and comprehensive COVID-19 coverage as the situation evolves by making a contribution.