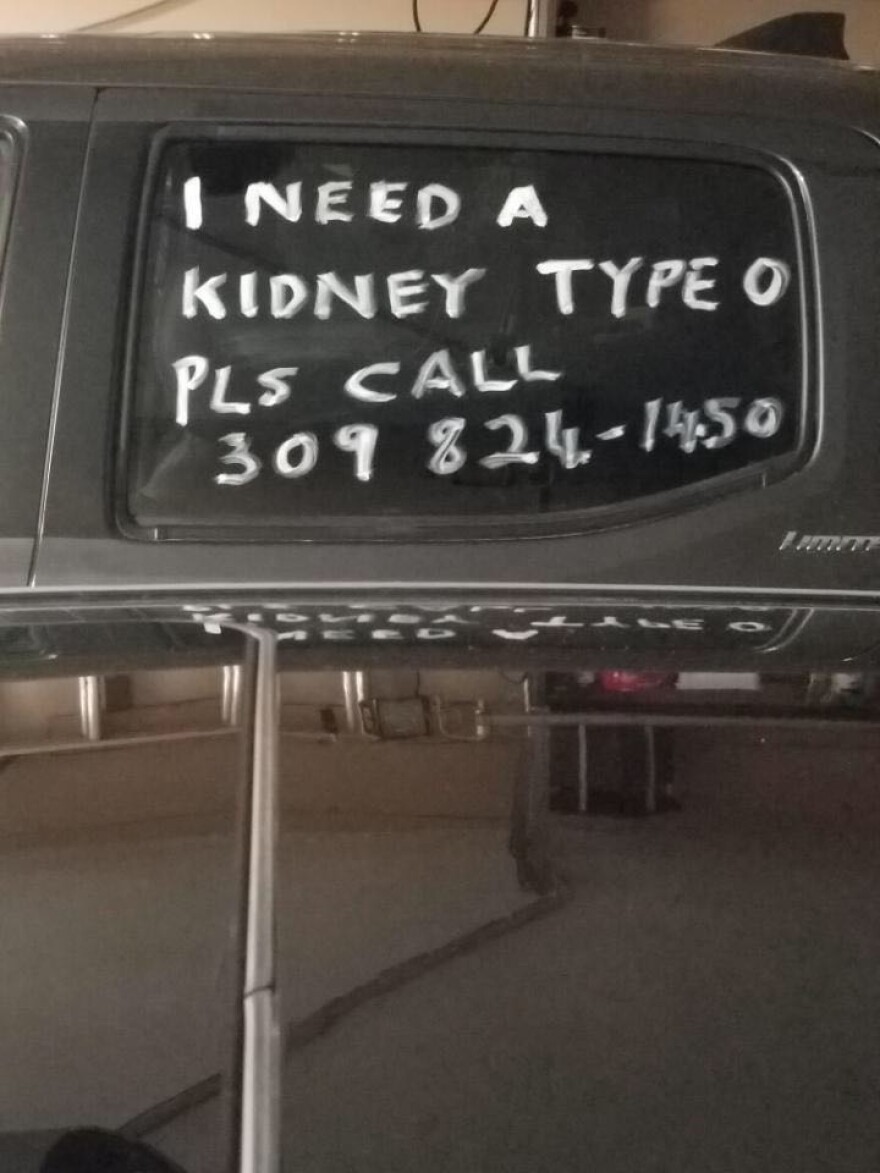

You might have seen a car driving around Bloomington with an unusual message written across its windows: “Need kidney. Type O.”

There’s a phone number, too.

Call that number and you’ll get Nisha Mohammed. The car is hers, and the requested kidney is for her husband.

The 66-year old lives in Bloomington with her husband Taj, 71. Both are retired: Nisha from a law firm as a legal assistant and Taj from the Clinton power plant as an electrical design engineer.

One year and four months ago, Taj had a major gout attack in his right knee. Doctors referred him to a nephrologist. Tests revealed Taj’s kidneys were working at around 30% of normal functioning. His kidneys were failing.

“Kidneys flush impurities out of your body, and if your kidneys are not able to do that, it kind of circulates in your blood,” Mohammed explained. “That really slows you down.”

Mohammed said that’s been tough for her husband, who has always been an active do-it-yourself kind of guy. Her husband’s nephrologist told them Taj probably had undiagnosed high blood pressure that eventually led to his kidney failure.

When Taj’s kidney function dropped to 15%, he became eligible for a transplant, and his nephrologist sent him to OSF Saint Francis Medical Center in Peoria. After extensive evaluation and testing, Taj was placed on a waiting list to receive a kidney from a deceased donor.

Mohammed explained the hospital will test Taj annually to re-evaluate his eligibility for transplant.

“He did good after his second evaluation,” she said. “He’s still on the list, and he’ll be on it until he gets a kidney.”

Today his kidney function is down to just 12%.

Mohammed said age isn’t a determining factor for transplant candidates.

“He’s 71 now, but his kidney doctor said he’s had patients who were in their 80s who’ve had transplants,” she said.

However, any sudden decline in his health could render him ineligible.

“That’s the scary part,” she said. “After one evaluation, they might say that he’s not [on the list] anymore.”

Taj’s situation grows more dangerous the longer he goes without a transplant, she explained. The couple learned that about half of patients placed on the list develop complications that disqualify them for transplant and die before they ever receive a kidney.

If his kidney functioning drops below about 8%, Taj will need to go on dialysis, Mohammed said.

“People have said that if you’re feeling so tired all the time and not doing stuff you used to do with as much energy, dialysis helps you, because it cleans out your blood and gives you your strength back,” she said.

But Taj’s doctor doesn’t want to put him on dialysis just yet.

“He said, ‘Once you get on it, you can’t get off it until you get a transplant,” Mohammed explained. “Once you’re on it you’re on it. So he wants to hold off as long as he can, watching him, testing him, make sure he is able to hold off as long as he wants him to.”

Mohammed wants to make sure her husband never gets sick enough to need dialysis.

“Considering his age, I don’t know how he’s going to do if he goes on dialysis,” she said. “That’s why I want to try hard and see if I can find a living donor, so that he doesn’t have to go through that.”

The waiting list at the hospital is to receive an organ from a deceased donor. For someone with Taj’s blood type, it could take anywhere from 5 to 8 years to get a matching kidney that way, Mohammed said.

Finding a living donor -- a healthy person with a matching blood type who volunteers to donate their kidney -- is their best option.

According to the hospital’s website, kidneys from living donors tend to last significantly longer than deceased donor kidneys. Some deceased donor kidneys also don’t start working right away, meaning the patient needs dialysis until the kidney starts to function.

Mohammed said hospital staff encouraged them to look for a living donor while Taj waits for a kidney from the deceased donor list.

“There is somebody out there who will want to donate a kidney to you,” Mohammed said. “How would you find that person?”

The hospital takes no active role in helping secure a living donor.

“Where would they start?” Mohammed said. “Every individual's needs are different. That’s why they encourage everybody to do their own part. Everybody’s blood type is different.”

Mohammed started with posting flyers throughout the community. Then she placed an ad in The Pantagraph.

The hospital does offer a focus group for transplant candidates and their families. Mohammed said that’s where she got the idea to write her phone number on her car.

A woman saw the message on Veterans Parkway, snapped a photo, then called Mohammed.

“She said I got this, and if you like I will post it on my Facebook so people will see it, and I said ‘Please do.’”

Mohammed said she doesn’t use social media, but she will now after seeing the results of the Facebook post.

“A couple of people have called me because of it,” she said.

One of the calls was from a man with type-O blood who was interested in donating.

“I gave him the phone number for the hospital in Peoria,” Mohammed said. “Then after a few days I texted him and asked, ‘Were you able to get through to someone at the hospital?’ And he didn’t reply.”

“I thought that he probably changed his mind, which they absolutely have a right to do,” she added. “It’s not an easy thing.”

When that happens, Mohammed said the only option is to stay positive and keep looking.

“I just take my time and do all this and expect people to respond, and understand that if four months goes by that you don’t get any response or reaction from people, that’s fine; at the hospital they tell you that can happen,” she said.

Mohammed cares for her husband at home while they wait. That includes making sure he takes his blood pressure medications, driving him to appointments, and helping monitor his diet.

“We cut out salt in our cooking at home,” she said, explaining that too much salt could cause excess fluid build-up. That could have negative effects on his heart and lungs.

Mohammed said for now, her husband still lives a normal life -- just at a much slower pace.

“He exercises everyday, still goes on his treadmill, pushes himself for at least 2 to 2-1/2 miles every day,” she said. “Those little things that keep him active. He's a gardener, but I told him not to go out this year.”

Because they need to be available should the call come in that a kidney is waiting for Taj, the couple can’t travel far from home, including to see their family.

“We are farthest away from everybody,” Mohammed said. “Our closest family are in Canada and California. We have two sons and they’re far away too, one’s in Seattle, and one is in India, but he comes and visits us.”

Mohammed watches transplant stories online to remind herself that people do find living donors.

“Sometimes people don’t even know each other when strangers donate until the surgery is all done; then they meet each other,” she said. “If you go on YouTube there are wonderful stories about kidney donors and recipients.”

“It’s a very special person [who] will do that,” she said of living donors. She recounted the story of Rob Leibowitz, the man who wore his plea for a kidney on a T-shirt during a family trip to Disney World.

“Somebody called them and donated,” she said. “All they did were T-shirts, and they got a kidney that way. So that’s how important this is, to go out there and make sure people see it.”

Now that warmer weather is on the way, Mohammed said she may just give the T-shirts a try, too.

How to help

Mohammed said even if someone cannot donate a kidney directly to her husband, they can help decrease his wait time through the hospital’s paired kidney exchange program.

The program matches up two sets of recipients with willing but incompatible donors who agree to donate their kidney to the compatible recipient.

“In other words, you’re going to save two lives,” Mohammed explained.

Those interested in becoming a living donor can reach Nisha Mohammed at (309) 824-1450, or remain anonymous by contacting OSF Saint Francis Medical Center in Peoria at (309) 624-5433.

WGLT depends on financial support from users to bring you stories and interviews like this one. As someone who values experienced, knowledgeable, and award-winning journalists covering meaningful stories in central Illinois, please consider making a contribution.