Kayla Bullock is a historian who was born in, and now lives again in Lincoln, Neb. Her family moved to Bloomington-Normal when she was in elementary school. She graduated from Parkside Junior High and University High School. She attended college in both South Africa and England.

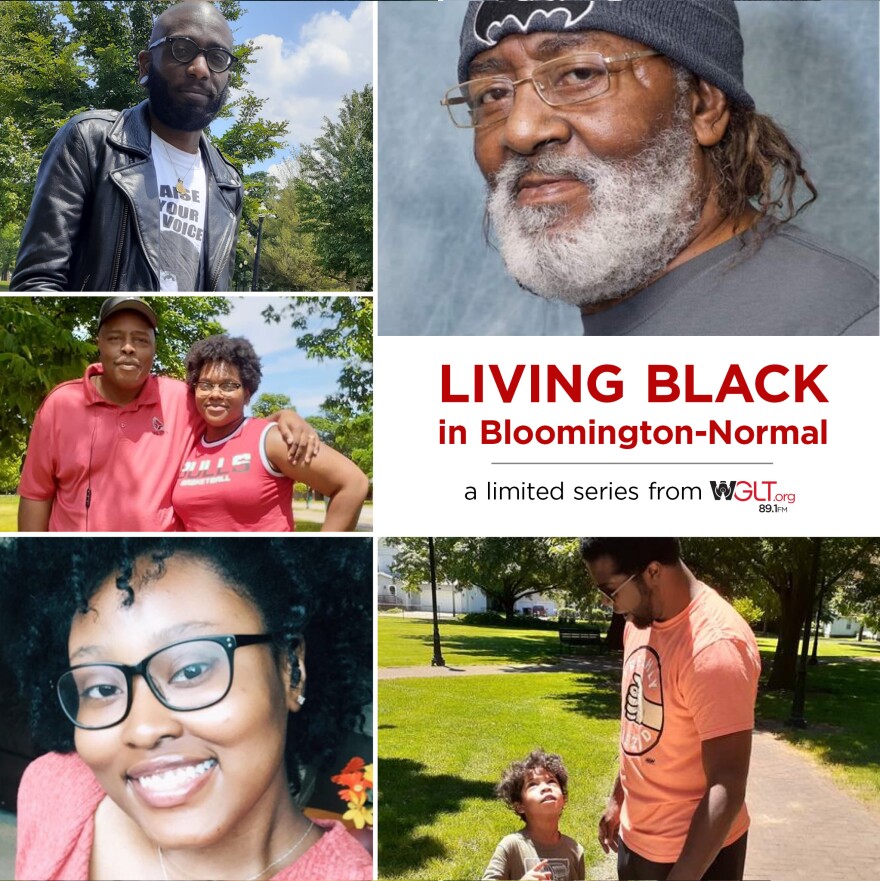

She spoke with Jon Norton for the WGLT series Living Black in Bloomington-Normal. Contact us if you'd like to be featured in the series.

Kayla, you identify as biracial. How has that identity played out among friends, school, work and neighbors?

It's hard because I've been constantly trying to fight for the white side of myself. Because I look Black. I look African American. And so I've been constantly trying to fight for my white side trying to prove to people that I am in fact, biracial.

Why is that important?

Because it's my identity. I grew up in a predominantly white household a majority of my life. I grew up in a very Danish and German home. And I like to keep that culture living. And it's something that's always been near and dear to my heart. And so I try to as much as I can keep that culture alive. I've just been that type of person to fight to prove to people for some reason that I am in fact, I'm not just Black. I’m biracial, I’m mixed.

How does that play out among maybe friends to start with?

It's played out in the sense of having to talk to them about it when they make inaccurate assumptions about who I am. You know, I've been called names like Oreo in the past. Black on the outside, white on the inside.

Who calls you that?

My friends. It's a term that I've grown up hearing. And it's something that when I was younger, I believed because it was a true representation. But it wasn't until I got older and I got to college and really started to learn about the culture and the oppression that I realized that that's not really a politically correct assumption to make about myself.

Could you give us an example of how it has played out maybe as a younger person, then as you became more aware of … that's not a term that you really want used?

So when I was younger, I usually just agreed with them and maybe laughed about it and said, “haha, yeah, you're right, you know … Oreo over here.” But now that I'm older, it’s more of sense of, "No, that's not correct. I'm not an Oreo.” I'm just a biracial individual who knows how to talk differently. According to people I talk more educated apparently, according to them.

I've had a couple of people tell me and they were young people like yourself, that when they correct their friends that their friends get a little defensive. Have you found that too?

I've had more defense come from my Black friends than I have my white friends. I've had friends tell me, “Well, Kayla, you just allow people to fetishize you.” And I would say, “Well, no, I don't. It's just the way they operate." And then we get into this big fight about what is fetishized mean and how does that work? But then with my white friends, they are more comfortable with understanding what I'm telling them and wanting to learn and wanting to move forward and operate on a different level. And so they are willing to understand and willing to, you know, move forward after being told. I've never really had a negative interaction with a white friend after telling them that's not a correct way.

Why do you think that is?

I'd like to think it is I surround myself with open-minded people.

You say you came to Bloomington normal from Nebraska when you were in what … third grade?

Fourth grade.

Can you talk about your memories of Nebraska? What town were you in?

I was in Lincoln, Nebraska.

How did it play out there?

Again, I was raised in a predominantly white household. So being so young and being kind of minimally exposed to African American culture was just not in my forte. It just wasn't something that I was exposed to on a daily basis. And so it wasn't until I moved here that I kind of exposed myself more to the culture shock of what is African American culture.

Could you talk about that exposure and how your mind expanded after you came here?

Yeah, and I don't want to say that in a negative way. But when I moved into junior high going to Parkside, it kind of was a culture shock, because I saw a lot more poverty. I saw a lot more of kind of that dynamic between white versus Black than I ever had before. I was put in a situation where I felt like I had to choose a side. And if I didn't choose a side, I felt like society was going to choose a side for me.

Did you choose a side?

I like to say I didn't because I fell in love with sports. And so I played volleyball for 12 years after that. I was a thespian as well. So, sports and drama kind of kept me from having to truly decide, but then again sports kind of brought me closer to my Caucasian friends because I played volleyball. So I was more adapted to that rather than my African American friends until I got to high school.

Could you talk about your time at U-High? What was the dynamic like there for you?

I graduated in 2014. And at my time, we had high diversity there. So, it wasn't just, oh, there's a lot of Black kids at U-High. It was a lot of Black kids that wanted to learn and wanted to be exposed to the highest possible availability of learning. So, I was surrounded by people just like me. And it was nice to kind of see that resemblance in not only the learning aspect but the cultural aspect as well … where you're kind of going through the same motions and you all kind of fit in the same grooves of things of, “Yes, we're Black, but we're not just Black. We're intellectuals. We're athletes. We’re people.”

You talk about navigating this world between being white and being Black. Have you experienced overt racism? Or is it more subtle like that?

There have been certain situations in my life where I've experienced blatant racism … very seldom though. Most of it has been that subtle hint where it's supposed to be a joke, but it's not really a joke.

One experience I had was actually here in Bloomington and we were actually just sitting at a Steak ‘n Shake. We were just hanging out. She had some guy friends come over to hang out with us, and they just immediately left. They didn't say anything … they just left. And later they called her and said, “Yeah, we just don't feel comfortable hanging out with colored people.”

What year is this?

This was … probably 2013.

Goodness.

Yeah. And that I think was the first time I ever was blatantly exposed to racism.

Let me switch topics. You attended the University of Essex in Colchester, England. Colchester is roughly the size of Bloomington-Normal. How do the demographics at that school break down?

Well, it is actually the number one most international school in England. So, high minority rights there. But you have more of like … international European than you do African American. And so I felt more judged on my nationality than I did my race, also.

How so?

I felt people judged me more of being an American than being a Black American. That was a good thing. Because I felt like it wasn't about my color. It was about my nationality. “OK, I get it. You're American.” It wasn't about being Black American, or African American. It was just, “You’re American.”

How did that feel for you?

It was an entirely different experience … than I've ever experienced before. And I traveled to South Africa and studied in my undergrad. And that is a completely different story. But it was just the exposure. It felt great to not have to constantly fight for something … or prove myself worth.

There were a lot of jazz musicians in the 50s, 60s and even into the 70s that left the U.S. and moved to Europe. Specifically, because it was a whole different way of being treated. Even though it was majority white in many of those places. It was still … they were treated much better than they were here in America.

Yeah, I definitely compare myself to James Baldwin, the writer who ran off to Paris and said, “You know, there's nothing worse that they can do for me there that that hasn't been already done to me here.”

How does that free up your mind or your emotional well-being … or your mental well-being to not have that weighing on you?

It’s … freeing. It allowed me to kind of focus on other things … focus on my studies a lot better. It was so uplifting, and it made me feel like I could do anything. I didn't feel judged and made me feel safe and to walk along the street and not feel like people were staring at me … for different reasons, you know it … it was just so … I didn't feel exposed.

Did you feel that you had more energy?

Yeah, definitely more energy to just go out and do … I wanted to go out … I wanted to do things … I wanted to be around people. London has such a high diversity rate as itself. You know, I wanted to be around people, and I wanted to experience the culture because I felt like I had a right to.

Are you implying that when you are here, you don't feel that same way?

Yeah, I would say at my age, and just how I've been exposed to it for so long, it's probably just a minor inconvenience, just because I've dealt with it for so many years. It's definitely a draining thing to constantly be on the lookout for people to judge you or misjudge you or to be … you know … the fear of someone saying something to you.

When you were in England and got to be a far from America, how did your home country look to you from over there?

Disgusting. (light laugh)

It looked like I never wanted to go back because I felt like I'd be moving backward. In a sense of … I made all this progress in my life and in the way I was experiencing life … that I felt that by going back I'd be going backward.

Let's switch gears a little bit. The last couple of months have seen major and multiple protests and outrage. It started with the killing of George Floyd. Have you been engaging in that process?

I've been keeping my eyes open and there have been a lot of protests in my town in Nebraska where I'm living now. I mean, there have been a lot of protests surrounding Black Lives Matter movement. And I'm not a protester. I'm more of an activist through academia. So I've just been reading the books and keeping up to date and really just trying to educate people as much as I can through social media, and posting books and articles and things like that … that will let people educate themselves on exactly what's going on … kind of the roots to the problem. It's not just something that started today. This started hundreds and hundreds of years ago.

As you've watched the protests unfold, what have you seen that is working? And what have you seen that is maybe not working?

I think violence is something that is shocking to me that doesn't work. I don't think anything comes out of violence. But what I do think works is the repetition … the repetition of constantly going out there and protesting … I mean constantly showing your voice … constantly being heard. It's what's going to get stuff done. But I don't think defacing monuments and destroying buildings and things like that are going to get anything done.

If you were in charge of making change, and you had a national platform to do something, how would you start doing this?

I would start doing it through education. I would start making the history of African Americans and the origins of Africans in America become a priority. Our history is so lackadaisical in our history books, it's ridiculous. Even, you know, from kindergarten up until 12th grade, it's the same knowledge. It wasn't until I got to college that I realized, “Wow, there's so much more to our history that I didn't even know existed.” That's why I dedicated my higher education to it.

Can you be more specific on that curriculum and how it might look in the schools?

I studied race all the way from the 10th century to the 21st century. It's something that has been present for centuries. And I think that starting it in 1619, with the first Dutch slave ship going into the Revolutionary War all the way through the Civil War … and then coming in through Jim Crow laws, Black codes … all that needs to be taught. Because it's modern history now … because we're going through it now.

In my area, I've kind of studied where exactly race and racism was created. That was kind of my interest. And I kind of went back to Colonial America. And so … my interest is … when did we create this social class division? And how can we go back and see this social class division and create a whole new social class where African Americans can be included? That's the problem … that when these social classes were created, and during colonial America after the war, African Americans were not included. So we've created a whole different social class for them. And now we're trying to integrate ourselves. But we can't do that, because we're in an entirely different social standing.

Nobody wants to admit what people did. Everybody wants to just kind of move on from it without healing. And that's the problem … that you can't heal until you admit the problem.

We’re living in unprecedented times when information changes by the minute. WGLT will continue to be here for you, keeping you up-to-date with the live, local and trusted news you need. Help ensure WGLT can continue with its in-depth and comprehensive COVID-19 coverage as the situation evolves by making a contribution.