Jen Brooks was born and raised in Bloomington. She worked at State Farm for a few years before becoming a language arts teacher. She taught at Peoria Manual High School beginning in January of this year and begins teaching at Bloomington Junior High School this fall.

She’s also a published author. Her credits include "Turning White: Co-opting a Profession Through the Myth of Progress, An Intersectional Historical Perspective of Brown v. Board of Education." She is currently completing a co-authored book titled “Mentoring the Mentor” through Dio Press.

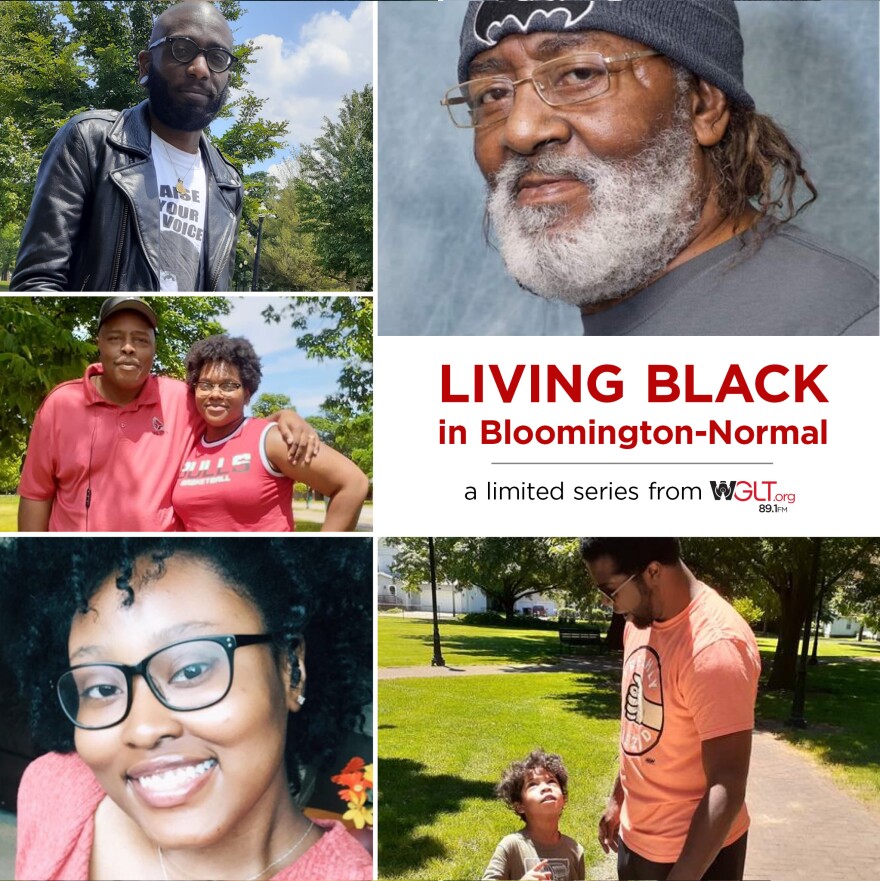

Brooks spoke with Jon Norton for the WGLT series Living Black in Bloomington-Normal. Contact us if you'd like to be featured in the series.

You're teaching at a junior high right now. And you wrote to us and said you had an incident that happened when you were in junior high that was essentially transformative for you. Before we get to that incident, can you set the scene? Who were you? What were you like? What was your environment like? What were your dreams before you got to that incident?

Always very driven.

Back in like my elementary school years, I did chess club. I sang in the choir. I used to do track … I did a little bit of everything. I was labeled gifted and was in accelerated programs back then. But very reserved, you know, I just did my work and I went home and helped with my sisters. And that was me. So, I never was like super conscious about race. Like it wasn't even a thing. I was just a girl. And I excelled in the things that I did. So that was just me … very low key.

What did you want to do? Did you have dreams at that young age?

I wanted to either be a journalist or a pediatrician. Until this incident in junior high, and I was like, “No, I can't do that, I want to become a teacher.”

What happened in junior high?

We were learning about African American history. And somewhere … what we see now usually is within the context of slavery, right? So, we learn …. as far as American history goes … the Black experience starts with slavery. And so, we watched "Roots" to, I guess, reinstall the concept. Keep in mind back then, it wasn't super diverse in the classroom. I was maybe one of just a handful of other Black kids. And so she asked me, she said, “So Jen, how do you feel about what our people did to your people?” as we finished watching the episode of "Roots." It was in that moment … I was like, hmm, I'm different. I'm Black. You know, like when they see me, they see a Black girl, and it's not like … you know, my parents … we knew we were Black … but it wasn't like in other situations ... like, "Oh, you know, I'm different."

Even now as I have transitioned into a teacher and do some community work … that is my focus. Representation is so important. Maybe had that teacher had friends in her circle that were Black ... or it was just obvious that she doesn't have the cultural knowledge to know that that was inappropriate. And thinking back on it ... like … “Black people, we aren't monolithic. I can't tell you how that makes Black people feel to watch 'Roots.' I can't tell you at 11 or 12, you know, I don't know.” But that was my first experience of being othered. And that's when I realized, I'm a Black woman, and that's what “leads.” You don't see just “Jennifer the girl,” you see a Black child in your classroom. And that's like my whole reason for teaching.

You are the third person I've talked with who mentioned they saw "Roots." And I think it was specifically junior high, it might have been Chiddix actually. For one person especially it was a traumatic experience … a very traumatic experience. Is that something that should be taught or shown in junior high? Or is there a better way to contextualize when it's being shown?

I think it depends on the teacher and who's teaching it. I think that our middle school students aren't so young that they don't experience racism. So, it's not like they haven't lived it. But if you're going to teach it, you need to have the knowledge and to let them know that this is not where your experience starts. “We're going to watch this, it may be heavy, let's talk about it.” You know, take breaks and work through feelings if you're going to teach it.

So, the way that that was taught to us it was kind of just dropped on our lap like … "this is a Black experience. This is slavery." You know, there wasn't any context before that, to let us know what we were about to see and what was about to happen. And "Roots" is intense, so like for young kids, that is a lot, especially if you don't have a teacher who has knowledge enough to really set the scene and set the stage and like, “you're more than just a slave,” I think that needs to come first, “before you came to this country, your people were engineers and doctors and mathematicians,” like that happens too, you know, so if we maybe start there and then transition … we just have a hard start at slavery, and that is traumatic.

That's a great point. It's easier to see you as a human being that way, isn't it?

Absolutely. But it's not taught that way. I'm not surprised that people said we watch "Roots" … I have a middle schooler and we watched the Central Park Five series together, because it's important content. You know, “this happens.” They were his age. My son is a middle schooler himself. And I'm like, we're going to watch this, but this doesn't define who you are. We're going to watch this so that you know other people's experiences and then we'll talk about it like teachers do. That to teach the hard stuff because it's so vital but teach it delicately. And that wasn't done for me during that time with that particular instance.

So, it was a transformative experience for you.

It was very transformative.

Was it almost immediately that you went, “I got to be a teacher, I want to be a teacher”?

Almost immediately. I knew that I needed to do something where people can be represented, right?

I've always been scholarly, I've always loved school. I've always excelled at it. And so I was like, "Yeah, this is it. I'm going to teach." And so as I got older … I had my son when I was 19 … and I'm like, I can't student teach and not work … I have this kid, you know, so I'm going to just work at “the farm,” (State Farm) … great benefits, great job and do that. But my soul wasn't fulfilled. Like I knew that that wasn't my journey. When I decided to teach I'm like, “I have to teach literacy. I have to teach reading and writing because that is yours … that belongs to you, you know, people can strip whatever they want from you. But if you have the power to articulate yourself and write down your thoughts and make them concise and make sense like that belongs to you.” And that's so powerful. And then again, I have to be … I want my students to look up and see, “Oh, there's a Black woman with some authority here. You know what I mean? Like, she can be somebody that we can look up to.”

When you “realized you were Black,” how did you start changing the way you viewed yourself?

I had to really dig deep personally, and find the beauty in being Black, because growing up in the 90s, it didn't create a space for you to feel worthy or valued as a Black person, right? What the media pushes out for people is typically like, if you're a Black woman, and you're “shaking your behind” somewhere … if that's what you do, that's what you do. Not knocking anyone. Or if you're a Black man, you're a thug or you're in jail. It wasn't a positive image.

I appreciate the times now because like they're transitioning and things are getting great, like being Black is amazing. But before when I was growing up, it wasn't that way. And so, just personally, I really had to do as much self-teaching, and really focus on like the beauty of the Black experience, so I would read things by like, bell hooks. I'm reading that again: "Teaching to Transgress." So that's a great book. My mom is from Alabama, and she grew up in the 60s. So I'm like, What is that about? What was that like? Just getting like some personal narrative to really explain who I am to really connect with that.

So back when you were in junior high … 15-ish years ago, what was the sensitivity back then compared to what it's like now?

Educators are more aware now, but research will show that we really aren't right. So we still discipline our Black kids way more often.

I guess I can talk about my son too. So he had this experience at his school and this touches on the sensitivity piece. And he kept getting in trouble. But every time he would get in trouble, it was something that was so based on someone's perception, right, and it offered stereotypical thoughts. And so I would get notes home. Like, “he's being aggressive.” “He was really aggressive today.” Or “he's very unfocused, we're having a hard time getting him to sit still.” And this and that. I'm like, so what are the other kids doing? I know, he's not the only one, right? And they're like, “Oh, no, everyone else is perfect.” He was also one of very few kids of color, and I'm like, OK, and so I would have to advocate for him and send a lot of sources and things like, we're not going to focus in on one mess-up for him and just make him seem like an aggressive, noncompliant child when he's basically doing the same thing that the other kids are doing in class. And so, I would slip in and not let them know that I'm coming and just watch them from the door. Because I wasn't there. So maybe, you know, there's some validity in what they're saying. And he would just be doing the same things as other kids. And … maybe this is like a case of bias kicking in, you're expecting this from him, maybe not. I don't know. But now I'm just super aware of it.

But I will say that most of the educators that I know are a lot more sensitive in their approach regarding discipline with kids of color. They try to make it … hard instances of “this is exactly what happened,” and leave your emotions out of it. I will say when I was growing up from what I remember, it always felt like my friends were in trouble. You know, we could be in a group of Black kids and white kids, but my Black boyfriends were always the ones being called to the office or getting kicked off the bus or doing something like that. So, I want to say that we're doing better as educators, but research will show that we are not. So, like I said, we were kicking out Black boys more. Now we've kind of transitioned to kicking Black girls out of school more. Again, based off of things that aren't hard facts, you know, like, we don't like their outfits or their shorts or t-shirt or their attitude sucks … really stereotypical thoughts that we have going on here.

I've talked to a lot of males over the last few weeks. And even when we did a series six years ago, there was a number of things that were common to what they were saying. Almost everyone will say, Yeah, I've had some kind of involvement with police, where they either feel targeted … stalked is a word that's being used. And I'm thinking about your son … how you talked about your son.

Mm-hmm.

What experiences do you hear from especially your Black male friends?

Upon doing this discussion with you, I let some of them know that this was happening and they were like, “Make sure that you mention that we do feel targeted and we do feel stalked," as you said. Several of my friends have been pulled over. And it may have been something just as minor as maybe they rolled the stop sign or did a couple miles over (the speed limit) … just something very trivial. But they have all been approached with guns drawn in their faces.

Every single Black friend that has confided in me about their interaction with the police, it's always been they are presumed guilty first, right? And when I think about my own son, he's 12 right now, but ever since kindergarten, we've been talking about how to interact with the police. And again, it's because at the end of the day his Black skin leads … that's what they see first. Throughout this interview, my son has just been sitting here mellow, chill, like that's who he is. But I worry about him going on a bike ride around our block, because, in an instance, he could fit the description as a Black child. And so, our Black men encounter the same exact thing and their treatment is so harsh. Like at all times. I'm pretty sure that other demographics don't have those same experiences. The guys that I know are very well-to-do men … like … they check all the boxes.

To be clear, Jen, you're talking about friends in Bloomington-Normal?

Friends that are right here in Bloomington-Normal or friends that recently moved away from Bloomington-Normal. But absolutely, yeah. Going back to the story about my kid and his issues at school. They're not one-offs. All of us cannot have the same experience for it to not be happening. We have to address these issues … we have to come to a middle ground and make it better.

Back to school. As a teacher now, what do you focus on? What do you do to make sure that representation matters in your environment?

When we're reading something, I try to include a diverse array of writers. We've been reading "Huckleberry Finn" and the same old things forever and ever. We can teach the same idea using writings from people of color, right? So, we need to give them places in our classrooms. I try to reach out to my community members as much as possible. If I have a friend that is really good at starting businesses, then I'll bring them in, talk to the kids, you know, I just want them to see themselves. I just feel like for so long, people of color have been pushed to the background, like, you can excel only so far … you can go here, but you can only go this far. So, I really would like to rewrite that narrative … like you can go as far as you want. And there's somebody that looks just like you who's done that.

I want to ask you something that series co-producer Darnysha Mitchell …when she learned I was going to talk with you … she wanted to ask this question. She's wondering what you think about Ebonics or the Black vernacular. As she says, nowadays, people try to call it internet slang. But often in schools, Black students are basically taught that it's not “acceptable” or “proper language” to speak. But it is embedded in Black culture. She said she grew up using it, she still uses it. But she had a teacher who always corrected her and made her say, and her classmates say things the "proper way."

Mm-hmm.

Thoughts as an English teacher?

My thoughts as an English teacher … Um, I'm still learning about this myself. But I totally think that African American vernacular is a language, and I feel like our Black kids are bilingual, period. That's what I think about it. And so, non-teacher Jen would say, “Don't code switch. Why are you doing that? Be your authentic self at all times.” But curriculum may tell me that there is a right and wrong way to speak. And I would say to that ... you have to let students know what type of English you are looking for in this moment, right? So, if I am writing a paper, I'm going to expect them to write using academic language. So however that looks, that's what we're going for. If we're just having a conversation and you want to use Ebonics, or talk to me like you talk at home? Do that. I don't think that's wrong. You know, I'm not going to diminish your language, which is a huge part of you and make you feel as if you're inadequate or you don't have the space here. We're not going to do that.

And I'm in my classroom, right? So, I would say, children who speak Ebonics are bilingual. If we need them to code switch to meet the standards of writing a narrative, then we'll write your narrative using academic language. And maybe we'll write another paper using Ebonics, you know, but I would never say “no, that's wrong,” because that's not wrong. That's how you talk, that is embedded in African American culture. It's in the novels we read. It's in the music that we listen to. That's not a wrong way to speak. It's just a culturally specific way of speaking.

You hinted at books and how maybe instead of Tom Sawyer ... Huck Finn, you can use another book to teach the exact same thing. Do you have any recommendations on some of the books that you might want to use in your classroom?

Absolutely.

So of course “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas is a really great book. Anything by Jason Reynolds is amazing. And it's not only written for Black kids ... like anyone can connect with these. My favorite-favorite book is called “Long Way Down” by Jason Reynolds. It is a novel but it's written in verse. So, there are so many lessons that you can do as an English teacher from that. It's about a kid from the streets. And he watched his best friend, who is his brother get murdered, right? And in his neighborhood, the rules are: never cry, never snitch and always get revenge. So as he is on an elevator going down to the first floor to get the revenge that he thought of getting, he's meeting people from the past on every floor who did get revenge, and it didn't work out so well for them. So, by the time he gets down, he has an awakening and he has to make a decision.

First of all, we have to get comfortable with being uncomfortable and trying different things. We have been reading "Huck Finn" and "To Kill a Mockingbird" … as far as literature goes … we are so beyond that. And we can be so inclusive. If we want to be ... you know … we have to be OK with doing something that's unsafe, and we have to be OK with getting a little bit of pushback. But as long as you can justify it … like what's in the best interest for our children, and how they see the world. I think we should really look into doing those types of things.

Some may say well, “those choices were certainly going to help kids of color,” right? But what does being more diverse in choices of reading in schools, even … what does that do for the white kids?

I don't want to sound like I'm excluding white kids, because I'm not doing that at all. But it gives them a realistic view of the world, right? Like when you walk through the halls and when you're out and about, you see all kinds of … normally … not now, you see this everywhere … it gives him a better representation of the real world. You know what I mean? It lets you into someone else's story that you may not have even thought … happened. You may never have had that experience. But just because you didn't have it doesn't mean that someone else doesn’t have it. It helps you to be able to empathize better and understand maybe why people's mindsets are different. It just opens you up to the realities of what is outside of your bubble … for all people … and not just white kids … it's for everybody.

So obviously, you're very passionate about making sure about representation about making change, affecting change. How are you going to do that?

I am as vocal as I can be at all times. And I feel like I have to do that, at the risk of it all. I feel like everything that I do comes from a place of love. And so I just stand on that. I'm not trying to harm anyone. I'm just trying to make it fair for everybody. I will say that I started a nonprofit. So, with the help of the team, and the Equality Pact, we have our foot down, and we are on the gas and we're going. We have a meeting with the chief coming up pretty soon ... the Bloomington police. And we have some initiatives with education going on. And so, we're really trying to do what's fair for all of our kids. And like we spoke about before, we aren't excluding white children because they are just as essential as everyone else. But we do want everyone to have a wider perspective and a greater understanding of each other, just so that we can finally move beyond this space that we're currently in as a nation ... like we've been fighting for the same thing for so long, we should really be beyond this right now. Right?

And so, just with the help of some really good people with the Equality Pact … people who are willing to just have these hard conversations, trickling in creative ideas, and different ways to teach in my own classroom is definitely something that I'm going for … and just continuing to be a voice. Like I will talk about it if no one else will talk about it, definitely create that space for myself and for other people just so we can all have equality.

WGLT depends on financial support from users to bring you stories and interviews like this one. As someone who values experienced, knowledgeable, and award-winning journalists covering meaningful stories in central Illinois, please consider making a contribution.