Subscribe to the new Harvest newsletter for our latest reporting on agriculture and the environment, behind-the-scenes exclusives, and more.

Many farmers are entering 2026 in a tight spot.

Crop growers in the Midwest and Great Plains are grappling with low crop prices. Scott Irwin, a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign agricultural economist, said there's been a stretch of general losses in corn, soybeans and wheat. Row-crop producers have lost a combined $34.6 billion this year before crop insurance and other support, according to the American Farm Bureau.

As 2026 approaches, Irwin said it’s a belt-tightening period for producers.

“Clearly the number one thing that everyone is mainly concerned is, where are prices going to go in the next year?” Irwin said.

Meanwhile, beef is selling for record-high prices, sparked by the smallest U.S. herd in about 75 years. Cortney Cowley, a senior economist at the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank, said the challenges for crops and livestock are opposites.

“On the livestock side, we don't have the supply to meet the demand, which is why we have such high prices,” Cowley said. “But on the crop side, we have too much supply and not enough demand where those markets become a lot more important.”

Across the board, producers are paying more for inputs like fertilizer and machinery. And many farmers have lost international customers as the ongoing trade war has disrupted export markets.

A September report from the University of Missouri found that farm income could fall by about $30 billion dollars in 2026 due to lower crop prices and a decline in government payments.

Irwin said many farmers in the Corn Belt have been surviving on a series of ad hoc payment programs from the federal government. Next year, producers are slated to receive billions in funding from disaster relief and economic aid programs – including a $12 billion bailout package announced earlier this month that aims to offset losses from low crop prices and the trade war.

Irwin said those payments could push farmers in Illinois toward a small profit instead of a hefty loss.

But, ad hoc payments only go so far, Cowley said.

“It’s not necessarily going to help the fundamentals of, you know, what do we do with the supply of the products that we grow?” Cowley said. “And what does that mean for prices that farmers are going to be paid on the market?”

New year, same trade questions

Economists say that trade uncertainty will continue to be a challenge as farmers make decisions for their operations this year.

Irwin is watching the U.S. relationship with China, the biggest buyer of U.S. soybeans, and the weather in South America through the first quarter of 2026.

Earlier this year, China boycotted U.S. soybean purchases for months to retaliate against the Trump administration’s tariffs. The country later agreed to buy 12 million metric tons of U.S. soybeans in 2025, and 25 million metric tons for the next three years – which is closer to what the country typically buys from the U.S.

But after the first Trump administration's trade war, China further diversified where it sourced soybeans, namely from South America. Irwin said Brazil is now the dominant soybean producer in the world.

“I think what people are probably as worried about as anything on the trade front is, how much permanent damage has this done in our trade relationship with China?” Irwin said. “Is this just going to be a repeat of the last 2017, 2018, when we permanently gave up market share to South America, principally Brazil?”

While the Trump administration has announced trade agreements with countries like Japan, Irwin said some of the details are still unclear.

"Maybe there will be some nice boosts in our agricultural exports coming out of these trade agreements. But we have to see more specifics and get down to that before we'll really know for sure," he said.

This is happening as tariffs themselves are in question. Currently, the U.S. Supreme Court is considering their future in a lawsuit.

For Luis Ribera, economic professor at Texas A&M University, trade in 2026 is hard to predict because it’s heavily political. He said markets don't know how to react to tariff unpredictability.

“In my world, that's the big question – is this the new normal? Is tariffs going to be a tool to negotiate with other countries? And looks like that's the way it's going to be,” Ribera said.

As other countries retaliate against U.S. tariffs and find other places to source products, some American farmers are putting harvested crops in silos. Ribera said that means farmers have to pay for storage, and they don’t know when crops can be moved.

He said the current market leaves few options for crop growers.

“Producers, they don't have an alternative or say, ’OK, you know, soybean prices are low, well, we're going to produce more corn, or we're going to go into cotton, or we're going to go into a different type of rotation crops just to take advantage of prices,” Ribera said. “I mean, all across the board commodity prices are low.”

A beef bright spot

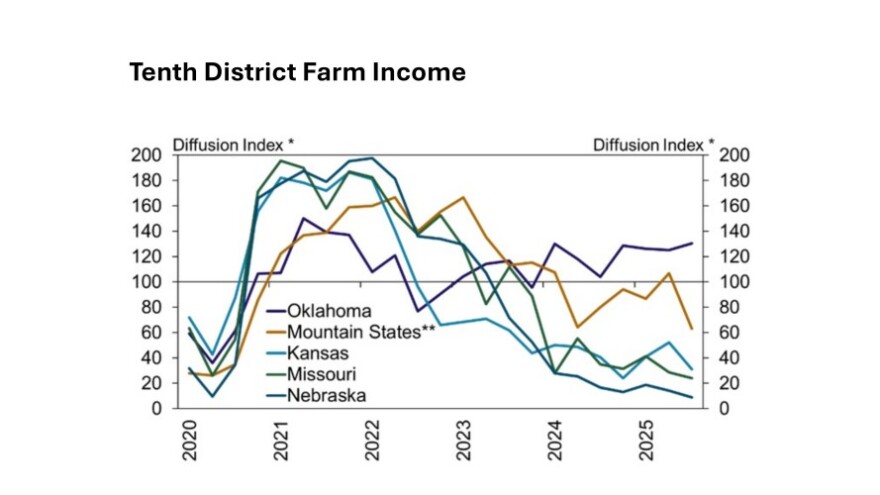

High beef prices in 2025 have helped to boost farm finances, according to a third quarter report from the Kansas City Federal Reserve.

Rough droughts caused the U.S. cattle herd to shrink to the smallest it’s been since 1951 and demand at the grocery store has not waned, spurring prices to an all-time high as producers sell cattle.

In states like Oklahoma, more producers have diverse operations, meaning they typically grow both crops and raise livestock. Amy Hagerman, an Oklahoma State University Extension agriculture and food policy specialist, said many of those producers can use beef revenue to make up losses on the crop side.

Beef producers are paying historically-high prices for cattle, but Hagerman said production costs like buying a trailer or building fences are still higher across the board.

“They (ranchers) just happen to have a product with a high enough price that they're able to maintain a margin, but margins really aren't much different for cattle producers right now than what they've been in the past,” Hagerman said.

She said producers have to be optimistic about the future, think in the long term and plan for cycles of highs and lows because it's the nature of their business.

“Even though we see some slowdown in the broader economy, we're seeing a slightly stronger slowdown in the agricultural economy,” Hagerman said.

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest and Great Plains. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.