The Morrisses have earned the right to relax in retirement as Black History Month legends and McLean County History Makers. But they're not relaxed. They're anxious about this moment in American history.

They point to states like Florida, where activists say new election laws and congressional redistricting have made it harder for Black communities to organize and vote. And as educators, they've watched as Florida's governor has signed laws recently that restrict what can be taught in Florida schools. The state’s education chief said a proposed AP course on African American Studies was “woke indoctrination masquerading as education.”

“These are very troublesome times. Over the years, I was very hopeful and pleased. But what is going on legislativewise is the opposite. Instead of opening doors, they’re closing them,” Charles told WGLT's Sound Ideas.

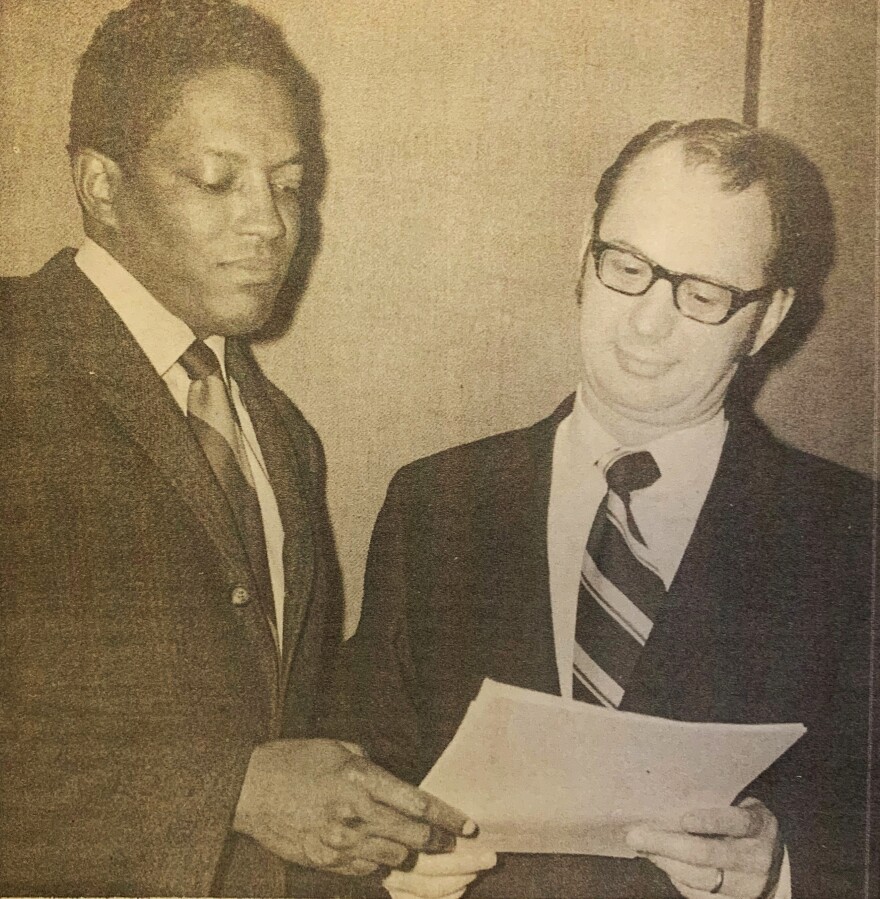

Charles and Jeanne – also known as Dr. and Dr. Morris – moved to Normal in 1966. Illinois State recruited Charles. At the time, he said there were only two full-time Black faculty members at ISU.

They were coming from Champaign-Urbana, where they had successfully pushed for passage of an “open occupancy” ordinance to make it easier for people of color to find housing. When they arrived in Bloomington-Normal, they found the same housing discrimination problem.

“So we dealt with ‘open housing’ there (in Champaign-Urbana). And when we got here – wouldn’t you know it – open housing was an issue in Normal. We did it again,” Morris said.

Charles and Jeanne remember well what it was like to look for a home to rent back in 1966. It’s not the kind of thing you forget.

“People would put their signs out. ‘For Rent.’ We’d go up and express an interest. No luck. One owner met us at the driveway and told us no, go away. We also approached a Realtor at the time about helping us find housing. No help from him,” Charles said.

The Bloomington City Council passed an open-occupancy ordinance in 1967, but Normal dragged its feet. Eventually, state and federal law did it for them.

Charles and Jeanne eventually found a place to rent, and they later bought property and built a home they lived in for 53 years.

“Open occupancy and breaking down those barriers which existed was something that occupied our time and interest for many years,” Charles said.

During this time, ISU’s Black students felt prejudice on two fronts – for being Black in a white town, and for being college students in a town with an uneasy relationship with its college.

And more Black students were coming in. In 1968, ISU launched its High Potential Student program to recruit Black students from the Chicago and St. Louis areas. Morris became director of that program.

“That program was significant in that it made a big change in the population here for students on the campus at ISU,” Charles said.

But those students faced housing discrimination when they tried to find off-campus rentals.

In the early 70s, the Morrisses and three other couples took the initiative. They bought four houses and rented them to students of color. For the Morris rental, Jeanne did all the work.

“It was like having several children, because you could administer to them and help them – and that was the satisfaction. They were good kids, and they wanted to do the right thing. My family just grew larger,” Jeanne said.

By then, Jeanne was on the ISU faculty too, training teachers and recruiting families for the relatively new Head Start early childhood education program.

The Morrisses took on a lot. They advised fraternities and sororities and the campus NAACP chapter. Charles became ISU’s first Academic Senate chair and later an administrator.

Some would understandably be overwhelmed by the weight of that. The Morrisses say they weren’t. It felt natural. They knew they had to be active to create change.

Charles’ father was a businessman who led Black people in Virginia to seek status. Jeanne’s mother was an elementary school teacher and principal in South Carolina.

“She made many changes, because she would not allow her students to be mistreated. One of the things she did was to change the distribution of textbooks that they’d give to the rural schoolchildren. They’d give them the used books from the white schools, until one day she said, ‘If I can’t have new books for my children, I don’t want any.’ And they said OK, and they changed the rule,” Jeanne said. “I don’t think we’ve ever asked for more. We’ve asked for equal.”

And for awhile, the Morrisses say it felt like things were going in the right direction.

They were inspired by new initiatives, like Illinois State University's Multicultural Center, which opened in 2021 and features a social justice library that bears their name.

They've been similarly impressed by the launch of the Bloomington-Normal NAACP's Youth Council, which formed in 2021 and recently completed a documentary about the Morrisses.

“Those youngsters are alert. They listen. They study. They’re the hope of the world. You have to get more of those,” Jeanne said.

But those young people are living in a cultural moment all their own -- and it's one that troubles both Charles and Jeanne.

“Things are different than they were in the 1960s, when were facing those struggles. Different even before the 1960s, when doors were closed completely. I couldn’t go to the University of Virginia, and Jeanne couldn’t go to the University of South Carolina. Those have been structural changes which are very significant,” Charles said. “There are still those who would deny systemic racism exists. Some of our public leaders in the Senate and, mostly, in the House are still denying that racism exists, when they are involved in trying to give it new life. Republicans are closing doors. Making it more difficult. That time of our life that we were in – we were very hopeful that the time had passed for racism to be so embedded in the culture of the U.S. But obviously that is not the case,” Charles said.

Added Jeanne: “We still have some of those instances that we have to deal with, at our ages. Where we are, where we live, where we shop – we confront some of those issues still. And it’s very maddening.”