It took more than 30 years to bring 110 mph passenger train service from Chicago to St. Louis. It could take that or longer to get true high-speed rail along the same corridor.

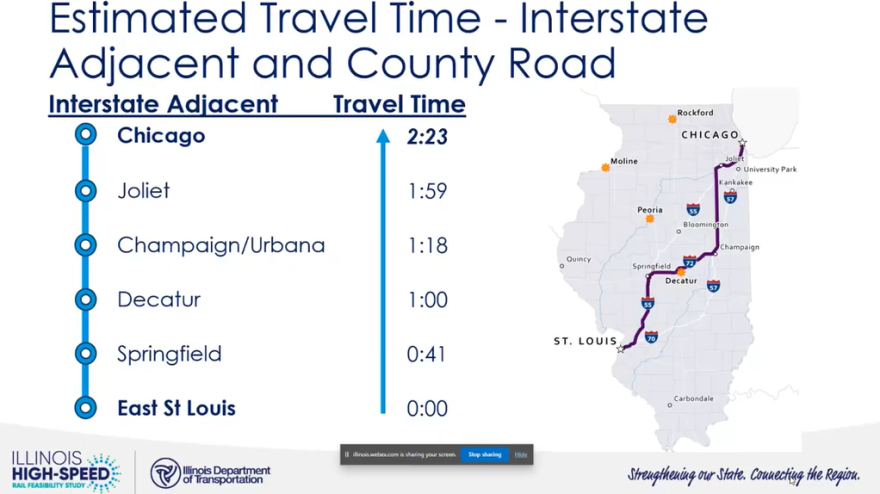

Imagine passengers going from Chicago to East St. Louis in about two and a half hours. Or Chicago to Bloomington-Normal, Bloomington-Normal to East St. Louis, or say Chicago to Champaign-Urbana each in an hour and change. Those are huge savings in driving time.

The Illinois High Speed Rail Commission supported by the Illinois Department of Transportation, is studying the possibility of high-speed rail along the Chicago to St. Louis corridor. There are several possible alignments. One skips Bloomington-Normal and goes to Champaign-Urbana, Decatur, and then Springfield. Another goes from Chicago to Peoria and then to Springfield. All the possibilities would use dedicated track, no stops outside major cities, and complete separation of grade crossings and crossovers.

Chris Koos, the mayor of Normal, sits on the board of Amtrak.

"The multiple billions of dollars that it would take do a high-speed rail line, regardless of the alignment, is pretty daunting, and a 15–20-year project," said Koos.

Eighteen other countries do high-speed rail quite well. Former U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood said, for instance, China, Japan and Italy all have 200 mph trunk lines fed by slower speed rail routes. And all have direct robust support of national governments, not just state governments

"Without that kind of vision and without that kind of financial commitment, we are way, way behind in America,” said LaHood.

During the Obama administration the nation took its first $8 billion step toward high-speed rail.

Over $4 billion went to California, which LaHood said has doubled that investment in the succeeding 20 years. Florida turned down a couple billion in federal money. Dallas to Houston has had a lot of work done on its proposed route, and the Trump administration could find plenty of private dollars if it wanted to commit to it, said LaHood. Koos said the current administration has pulled the plug on that study. In Nevada, the Biden administration plunked down $3 billion on a Las Vegas to LA route.

“So, the initiative that was started by President Obama with his vision for passenger rail is moving along, not as quickly as we all would like, but it’s happening in America,” said LaHood.

And even though the San Francisco to LA effort under construction is "way over budget and taking too long," LaHood said it will also be a win.

OK, back to Chicago to East St. Louis. The study will take a while. Koos has his doubts.

"I see it to be visionary, but I don't see the economics of it working at this point in time," said Koos.

He said the amount of land acquisition would be incredibly high for a green grass route.

"It'll be interesting to see what a private organization, Brightline, is trying to do in California where they are trying to leverage existing land along an interstate and if that works, that may be a solution. Then it really narrowly defines a corridor," said Koos.

Part of the Illinois study does consider using highway right-of-way — and even county road right-of-way in some spots. Consultant Charles Quandel said it will also be important to use electric propulsion like the Japanese Shikansen bullet train instead of the engines Amtrak now uses. The rate of acceleration is faster with electric.

"Current Amtrak equipment that's diesel-powered, it takes about four miles (to reach) at its top speed. In contrast with the catenary electric propulsion, they're able to hit that same speed in just about a mile," said Quandel.

The current Chicago to St. Louis corridor through Bloomington-Normal already helps passengers who would rather not drive that distance. Joe Szabo, a former head of the Federal Railroad Administration, said the competition is different for 220 mph service.

"In 220 what you are looking to do is to be superior to air,” said Szabo

Szabo believes in a passenger rail program in which you connect 220 mph service for major markets with minimal stops to a 110 mph regional network and feeder lines into that network that travel at a traditional 79 mph. All those routes need to connect to form the same kind of comprehensive transportation network used in Asia and Europe. And understanding how the aviation market connects is important.

Szabo said 220 mph can be used to shift passenger demand to rail.

"When you are talking about a distance of 500-600 miles, that's kind of the sweet spot for 220 mph service and it frees up that capacity in the aviation network for the longer distance flights which are much more efficient in the longer distance," said Szabo.

It's possible the airline industry might not see it that way. The ongoing Illinois High Speed Rail Commission study is trying to gauge whether people want 220 mph service by doing a variety of surveys online and in person.

Rhett Fussell is a transportation engineer with the consulting firm WSP. Fussell spoke at the May commission meeting.

"O'Hare and Midway, those both agencies refused, the airport lawyers refused, to allow us to do surveys on the airport property and so did St. Louis," said Fussell.

The commission does have more than 6,000 responses to surveys. Illinois Department of Transportation Transit Planning Manager Hannah Martin said comments are mostly positive so far.

"We've got a lot of support coming in for the route to include the Champaign-Urbana area. We've also had some support; a few folks have mentioned Decatur and Peoria. There are comments saying, make sure that this is efficient when you talk about a feeder network. Train to train is better than train to bus," said Martin.

There are other ways to get at the question of market demand: studying population, strength of local economies, how those economies complement each other in business and industry, and how they connect to each other via air. That all factors into the choice of where to put 220 mph service. Koos said let's wait and see because the economic studies haven't yet been done.

Both Koos and Szabo suspect that, on the surface, Chicago to Minneapolis might be a better fit for the first true high-speed rail in the Midwest. Szabo said Minneapolis is a stronger population center than St. Louis, and it may be a better fit with Chicago. Szabo said it will be important to make sure nobody puts their thumb on the scale in generating those studies.

"That's kind of the million-dollar question, isn't it? Because you really do want to try to make certain there is an honest assessment based on population and economies," said Szabo.

The cities of Champaign-Urbana, Decatur, and Peoria are all very interested in having a stop on a potential 220 mph service route. One government official said get your popcorn and settle in to watch the politics happen.

Szabo said the answer to political infighting is to make sure everyone knows they won't be left behind.

"Everybody wants the big prize, but perhaps they're not the best example for the big prize, right? But that doesn't mean they should be left alone and left isolated. It comes back to this interconnected network, to make sure that the citizens of all these communities have quality connectivity to the broader system," said Szabo.

Szabo said in order to really show that ridership is going to be there for 220 mph service between Chicago and East St Louis, it's going to be important to continue to grow ridership on the existing 110 mph service.

"And in my mind, it is very important that it percolate up from the grassroots. That's what elected officials respond to," said Szabo.

Former Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood said, "There are certain big things that always have to get done and it depends on the leadership at the time."

And wherever Midwest high-speed rail happens, LaHood said, it will have to be a public-private partnership because of the expense.

"You can't do any of these projects simply with federal or state dollars," said LaHood.