When there is a large concentration of birds, disease tends to spread. This winter was an exceptional winter for finches coming down to central Illinois from Canada, and that caused more birds to be at feeders than normal.

American Birding Association magazine editor Michael Retter said the disease most prevalent in McLean County is salmonella.

“Here at my feeder, we’ve had lots and lots of Pine Siskins and there is a big salmonella outbreak in this area and I’ve probably seen eight or nine dead Pine Siskins in the last couple months, but it's not related to cold,” said Retter.

Pine Siskin is a small species of finch.

Retter said the higher concentration of finches from Canada can be attributed to failure in cone-seed crops in Canadian forests last summer.

Retter advised keeping feeders clean with a diluted bleach solution. If there is a salmonella outbreak it may even be a good idea to stop feeding for a couple of weeks.

Salmonella can build up on the ground around the feeder as well.

“There are one or two species that show symptoms more,” said Retter. “Pine Siskin is a classic one. A lot of people see Pine Siskins at their feeder, the other birds will all fly away and then there’s one that is still sitting there with his feathers puffed up and its eyes are kind of half closed, maybe even sunken in. That is a classic sign of salmonella.”

There are other species, like the dark-eyed junco that presumably come into contact with the bacteria. But Retter said he’s never heard of one succumbing to the disease, or even showing symptoms.

Retter said there is a huge Pine Siskin population, and the salmonella uptick can be attributed to that quantity.

“We’re not used to seeing huge numbers of that species, so we are not used to seeing the presence of salmonella,” said Retter. “When we get these large concentrations of birds, diseases tend to spread more readily just like people.”

Cold snaps and their effects

Really intense cold snaps tend to affect insectivorous birds, which are birds that depend on eating insects. Retter said the cold snap that only recently lifted could cause certain species to kick the bucket because they can’t find enough food.

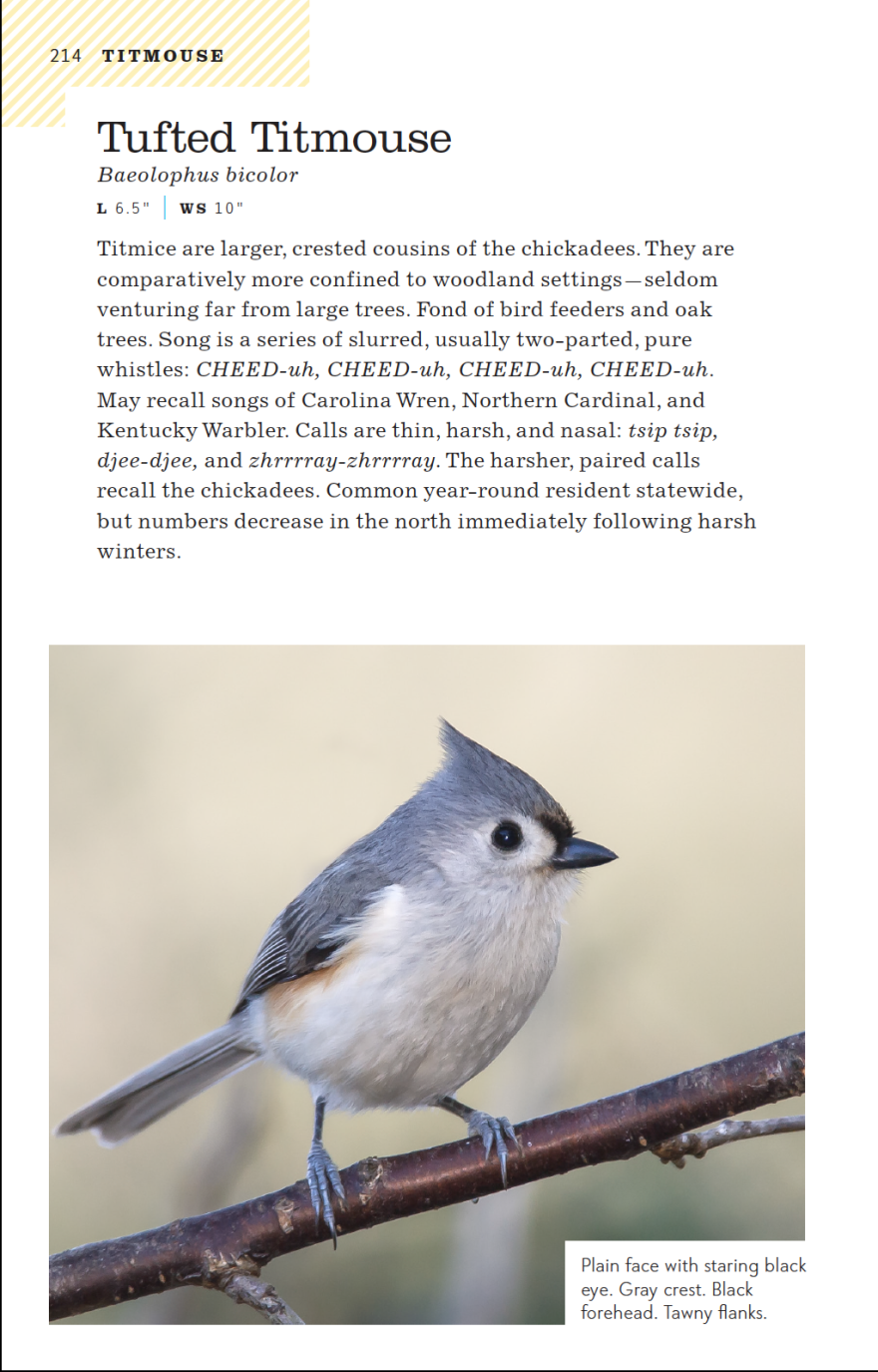

“Carolina Wren, Tufted Titmouse, Northern Mockingbird are three birds that are kind of towards the northern edge of their range, and when we get a really hard winter their numbers decrease a lot,” said Retter. “You may have a pair of Carolina Wrens that have lived there for six years, but after a cold snap their gone.”

McLean County doesn’t have a lot of insectivorous birds through the winter; most leave if it gets below 15 degrees regularly.

There is a species called fish crow that showed up in McLean County about seven years ago. Typically, that species is found along the really low river valleys. For some reason they appeared in Bloomington-Normal.

“As far as a reason, I could only speculate, is that it is climate change. As the planet warms, birds’ ranges tend to move towards the poles and away from the equator,” said Retter.

The fish crow has been found in Ontario and further north compared to where it is known to be found historically.

Retired Illinois State University biology professor Angelo Caparella said the cold snap was only enough to affect individual birds and not populations. What is even more worrisome, he said, is the weather getting warm too fast.

“If it gets warm too fast, it starts affecting the timing of blooming plants and the associated emergence of insects. That can really throw off the food supply timing for birds,” said Caparella. “I’m always a little worried when we get too early of spring, we’re getting earlier springs anyway due to climate change. If it's truly way above the norm, that could be a factor in breeding success down the line. I’m hoping we’ll get back to more normal temperatures and gradually ease into normal spring breeding temperatures.”

Caparella said if we don’t do anything about climate change, Illinois in about 50 years will have a climate similar to that of east Texas.

“That will cause huge disruptions to everything, from animals and plants to agriculture and people,” said Caparella. “We are on the verge of seeing these kinds of climate swings become really serious.”

Retter said the best thing residents could do for helping central Illinois birds is to cut down on the amount of pesticides sprayed on crops.

“About 70 years ago, when we weren’t spraying corn fields three or four times a summer like we do now, bird populations were much more robust,” said Retter. “I think there are less than 50% of the birds now compared to when we were surveying them 70 years ago. It has really taken a toll on insectivorous birds.”