Kevin Graham was born in Springfield and moved to Bloomington at age 3. He says he grew up “on both sides of the tracks," first in the Sunnyside projects in west Bloomington, then in Lancaster Heights apartment complex in Normal. He attended Sugar Creek Elementary, various Catholic schools in Bloomington-Normal and Springfield, Chiddix Junior High for one year and graduated from U-High.

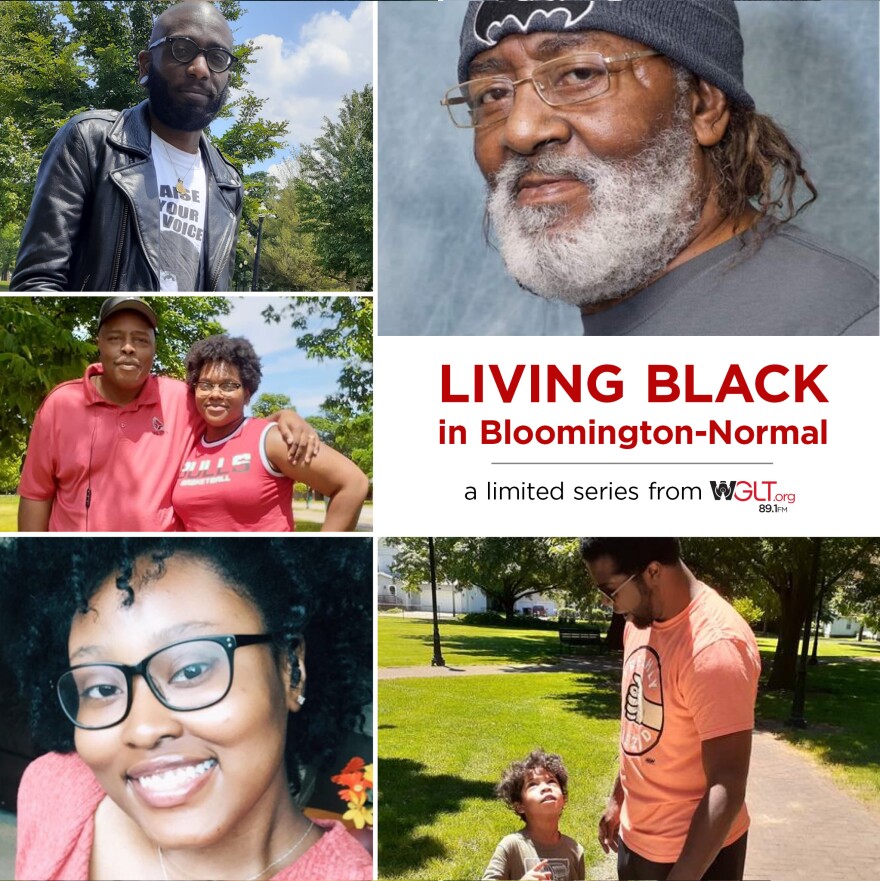

Graham spoke with Jon Norton for the WGLT series Living Black in Bloomington-Normal. Contact us if you'd like to be featured in the series.

You weren't born here, but you have been here pretty much all your life.

Correct.

You and your family are almost the definition of a townie.

Oh yeah, considering my grandfather goes back to 1891 I think is when my great-great grandfather moved here. Dr. Eugene Covington. He was the only Black physician in Bloomington-Normal at the time. If I remember right from the family history, he started the Republican Party ... something with the Republican party and voter registration for African Americans here. He had a clinic. His office was actually on 310 North Main Street in downtown Bloomington. He lived over on East Market Street just a few blocks from there. His original wife passed ... he married one of the Thomases, so that's how we became relations with that side of the family from here in town. He wasn't allowed to practice at the hospital, Mennonite at the time. And at the time graduated from Howard University's med school in D.C. His parents were slaves. He was born right after the end of the Civil War. He attended Catholic schools and I believe it was Philadelphia because he had such a high intelligence level.

Was that unusual back then for a Black man to be in the Catholic schools?

Yes. It's almost unusual still today. (laughs)

You hinted at when he was a surgeon, that he couldn't perform surgery …

Without having a white attending physician standing over your shoulder. So that's kind of one of the weird things where the white attending physician sometimes wasn't even a surgeon. You just had to be a white physician who was checking over his shoulder for something he didn't even know about.

Did those stories get passed down the family?

Yes, also Caribel Washington did a family history because my great-great grandfather actually delivered her. In the McLean County Historical Society, there is a section for Dr. Covington.

He was also an obstetrician?

Yep. He delivered pretty much most of the Black community. I mean, there was a thing in there that I remember reading where it was said that there were some white physicians who were trying to undercut him, as far as price, to run them out of business. And he complained to the medical board here in town, and …

What years are we talking now … Was he practicing?

Let’s see … he passed in (19)31. So, it would have been from 1896 to I want to say 1931, because I know on the cornerstone of the AME church on Center Street … by Holy Trinity … I want to say that was built in 1908, and his name is on the cornerstone of that building.

So, he's one of the founders of the AME church in town.

Correct.

That’s a storied history.

Yep. That's my Dad's side of the family.

What else you got for history in the family here in Bloomington-Normal?

My grandfather was the first Black police officer in Bloomington … Doc Covington.

What year was this roughly? Or what years were these?

He passed in (19)57. And I want to say he started with the force in (19)32.

That’s a lot of firsts for your family.

Yeah. And then I kind of slid the bar down a little bit. (hearty laughter)

Well, let's talk about you a little bit Kevin. Why did you want to talk to us?

We've got a lot of unrest going on in this country right now. And it seems to me like a lot of people are following in political footsteps and doing a lot of deflecting of real issues. Why is it that we can't all be equal in the country that we all built? I mean, some of us have died in every war, as far as people of color. We've sacrificed. There's no reason that we shouldn't be able to find some common ground and admit what's been historically wrong with our country, which is equality.

Why is that?

What I'm finding is a lot of my friends … white friends … throughout my lifetime, have become complacent. Oh, you know, we have “the one.” “We have a few of our friends who are Black.” And they're not willing to look outside of even McLean County. I mean, we're pretty insulated here in McLean County. Yes, we have some issues. But compared to other places we don't, as far as the deep-rooted problems. And so, people don't want to get out of their comfort zone. They don't want to get out of the bubble. It's going to require pain on everyone's part. It's not just people of color who need to proclaim and march in peace in what they do. But they must also be willing to compromise in some things. I mean, we're not going to get freedom and equality overnight. We haven't done it in 400 years. We haven't even done it since the Civil Rights … I mean, it's something that's gonna take time. But you have to go into it with an open mind.

I want to switch gears on you. You talked about your family's history in the Catholic Church. You mentioned to me when we initially talked that you went to Catholic school here in town. Could you talk about going to Catholic school and probably being one of the only or few Black people in that?

Yeah, pretty much at Epiphany I was the only Black child and there was a lot of the N-word used to the point where we talked with Father King at the time, who was the head priest, and it took some persuasion to finally get him to even speak up a little bit. I thought, you know, Epiphany wasn't the place, so we went and tried St. Clare. Pretty much the same issue happened there at St. Clare. But the difference was, Father Deitzen put his foot down after a while and said, “You know, enough is enough.” When I got over to Holy Trinity it was a lot different. I didn't hear the N-word word nearly as much, but I still heard it … still felt it. You don't have to hear the word … you can just tell by the way people act and their body mannerisms. I mean, the one thing that people of color have kind of become accustomed to is reading people in some regards as to race relations. Because in (19)72, through about (19)78, if you walked down the street, someone would call you the N-word ... here in town even. I want to say it's almost like it became closeted when affirmative action kicked in and all that, and people of color started getting a little more clout politically, here in town, it became closeted. But you still knew it was there. I mean, there are some prominent business owners who refused to have anything to do with people of color as far as in their family, but yet their businesses were in the Black community.

When you talked about the N-word being dropped in your Catholic schools, was that just the students you're talking about?

Yeah, I've never heard a nun or teachers say that. Yeah, I can't say I've ever heard those words come out of … but when something happened the blame was quickly put on me rather than others. Like if an incident happened on the playground, “Kevin, why did you do that?” (He would respond:) “Did you not hear them say that word?” I mean, after a while, I got to the point where I was kind of physical about … I mean, I fought a lot as a third and fourth grader more than I should have.

What do you mean you're supposed to do something about it?

Well, you would think that if the nuns on the playground … they hear it, they would walk over and stop it. Not doing that and eventually you get to the point where you know, I put up the right hand and turn the cheek for too long. And then finally, enough is enough. If you want to call me that, I will take it out on you … extract my pound of flesh. Which was not the way to go, you know, but as a child, you kind of have to learn your ways through things, and anger was something I had issues with it at one point time because of that.

Do you think you would have had anger issues otherwise?

No, because growing up biracial, which I don't think I have mentioned yet. I have a Black side of the family and white side of the family. I've always had to learn to walk a line between both cultures. And both societies. I mean, because Black culture ... Black society ... is completely different in a lot of ways than white culture and white society. So, I've learned to navigate in between, which means you do a lot of accepting … a lot of taking things and say, Hey, you know, it can be better.

That's an interesting thought that you have to navigate between these two cultures because you are those two cultures as opposed to, if you're considered Black or you're considered white, you don't have to navigate it the same way. Can you describe the difference and how maybe you had to navigate that?

Like in my family on my mom's side, which is white, they are doctors, lawyers, physicians in Springfield. I mean, they are upper class and so not only was I learning to navigate in two worlds, it was almost like three worlds because socioeconomically, there's a lot of difference between living in the projects and then going to your grandfather who has lots of money. (He's) very powerful in Springfield because he founded the Springfield clinic. My family's history on my mom's side … we've had congressman, doctors, lawyers, architects, you name it, we've run the gamut on the high end of the economic spectrum. And then I remember going to my Grandpa’s … one of their anniversaries and I didn't have a suit jacket. And I got crammed into a suit jacket for the family photo. So, I'm like busting the seams out (laughing) because I'm so big trying to wear my grandpa’s (suit), but you know, who has $100 for a suit when you're living in projects?

Was there even some racism in my family? Yeah, my grandma … I love her to death. But you know, what she did with my other cousins … she did not do with me. And the only difference between my other cousins and me was the color of my skin.

What were some of those things?

Like for every birthday, she’d take them to McDonald's or do something nice with them. I got a card. I mean, granted, I liked getting a card with a check in it, but you know it was my grandma's way of … so I even learned about closet racism on that end in my own family. And like on the Black side. Well, you know, you're … you're almost too light for the Black people, you know, you're too dark for the white people. That's kind of what I'm saying as far as navigating in between, you have to make your own way.

I mean, you're not that old.

I'll be 51 this year.

OK. Still. That the N-word was thrown around pretty liberally when you were in public school, as well as parochial schools. And you said that, at first, you didn't get a lot of backup from the administration.

No.

And you're out there all by yourself anyway, in school. What does that do to you? How does that change how you view school? How does that change how you view what you're doing right then?

Well, you don't spend a whole lot of time concentrating on school. (laughs) You spend a whole lot of time concentrating on, can I get through this day, the next day without slapping someone … hitting someone. Being called to the principal's office. So, I mean, just that alone, detracts you from the school part of it. I mean, I can't imagine how people even two generations older than me, like in their 70s could grow up in the south. I mean, I didn't catch it nearly as bad as they did. And it either makes you or breaks you … you're either gonna become stronger from it and learn to self-identify with yourself and your type and say, you know, “Forget it they're not worth it.”

Or you're going to get angry about it. And far too often, people get angry, and I got lucky where I had some good mentors on both sides of my family and friends. I kind of have an extended family here in town. There's a lot of people in the Black community who have taken me under their wing ... like Marshall Howard. I call him my uncle. The Thomases. Buzz Thomas, Gloria Thomas … the Gastons. They took me under their wing, and they were more, as we say now, upwardly mobile Blacks. They had money, they had education. And that's the main thing I found that it seems like education, to a large extent, plays a role in racist behavior and racist attitudes. Because as you get to a university level, your horizons are kind of broadened. You stay in high school, you're kind of stuck with what you have right around you. When you get to that level. It's usually an intermingling of everybody. Doesn't matter race, I mean you've got people from all over the world at a university, so your horizons get broadened and your attitudes change.

People are protesting … people are saying this is enough. We're seeing this … it looks like more than we've ever seen it. It looks like it's sustaining itself somewhat, even here in Bloomington-Normal. What still needs to get better?

Our policing and our judicial system, plain and simple. If those things got better, I think a lot of people of color wouldn't be so on edge. I mean, for me, I'm past this point, but between the age of 16 and 25, I had 116 traffic stops. I'm not a bad driver. The wrecks that I was involved in were not mine. I never hit anyone. They hit me. But I was definitely on that list of things where they were profiling. I was driving while Black. I had nice cars and nice motorcycles. I had loud music.

What would you get pulled over for?

“Oh, you ran the stop sign.” The officers three blocks away from me. There's a big pile of rubble sitting in front of the stop line, but he saw it. I had made the mistake when I turned … when I was 16 … I had a motorcycle and I rode my motorcycle before I got my license. Now, I admit my mistake. I got stopped…. I got a ticket for it. The next day I went down and got my motorcycle license because you know … so I had one cop … and this was when I was at U-High … who for almost two or three months straight, every day I came out of U-High … he was sitting … because I lived on Hunt Drive and I would take Fort Jesse or Willow home. He'd be sitting over around School Street or Normal Avenue. And he stopped me. This was like three months, almost straight every day coming out of school. And so, “Haven't you figured out by now I got a license?”

But what was he stopping you for?

“You did you didn't come to a complete stop.” “You didn't do this.” “You didn't do that.” I wouldn't get a ticket. But he'd stop me. There are other times where I get pulled over, I wouldn't be issued a ticket. “But how do you have this car, Mr. Graham?” That's called hard work. Little did they know that from the time I was 11 until I was 16 I was waxing cars for a mom every day because we had a business called Mary's Pretty Cars. I spent my summer waxing cars when everyone else was out playing, making money.

Let me be clear, they asked you …

How you have this car. You got to remember something. Our judicial system gave them the right to do that. Because they thought that by stopping people and having a quota system for police officers, you deter crime. What are you really determining? I mean, most criminals aren't gonna be crazy enough to be driving 90 miles an hour down the street. Most criminals aren't Black by the percentage of the population. Remember, African Americans only make up 13.7% of our country. But yet we're 66% of the incarcerated population. So why is there such a disparity number between that? It's because they spend all the time policing in the Black community, not the white community. I mean, if you go sit down on the west side of town, I'd be willing to bet you'd see 12 or 13 squad cars go by. If you went out on the east side of town, like on Airport Road, how many squad cars do you think would you'd see drive by? Zero, maybe one, two, unless they were called out there. So, if you spend all your time in one area, yes, you're gonna find crime.

So, what you were talking about getting pulled over, over 100 times when you were younger. So that is 30 … 35 years ago. What is it like today? How would you describe it?

I mean, I bought my son an older Lexus when he turned 16. Well actually 17. It's a white car, and it gets hot in there. And when I went to get the windows tinted I was thinking of him specifically because I said, “Do not take anything less than the law." Because the last thing I need is for my son to be harassed like I was.

So, I still make decisions based on how I was treated even with my kids today. Should that have to happen? Heck, no. I mean, why should I fear about my son driving a car when I know my son's a great kid, on the honor roll at NCHS. He's on his way to West Point ... played bass in the school orchestra. Great kid. But me knowing how I was treated in this town, I made sure it wouldn't have to happen to him.

Does that happen to him?

No. That's one thing where I can honestly say … because I'm mixed and my ex-wife was white, my son does not look very much like me as far as color of skin. So, if he was walking beside us right down the street, they would never think twice about it. I thought about this statement that I made. When my son was born. I was like, you know, my son will never have to face the issues I've had, because of the color of his skin. And as a father that says a lot. I mean, when you think about … because of the color of my son's skin … he won't be harassed. He won't be killed. He won't be called the N-word … he won't have to live through what I lived through. And the only difference is he's a very light-skinned person. But remember, by the government standards, if you're 1/8 Black, you're still Black.

Now … I just brought that up, but I kind of teared up a little bit inside because … that's pretty messed up.

WGLT depends on financial support from users to bring you stories and interviews like this one. As someone who values experienced, knowledgeable, and award-winning journalists covering meaningful stories in central Illinois, please consider making a contribution.