Mark Gardiner stood on the hill he calls "the high and lonesome” on his 48,000-acre ranch.

The lookout near the Oklahoma-Kansas state line opens up to a sea of sagebrush prairie, a hospitable home for deer, badgers, songbirds, dragonflies and other wildlife.

Those who stick around long enough on the Gardiner Angus Ranch may also spot a lesser prairie chicken.

“I love them. I like seeing them,” Gardiner said. “I mean, you're riding a horse across here and ever since I was a little kid, they fly off like a pheasant … it's pretty cool to see them.”

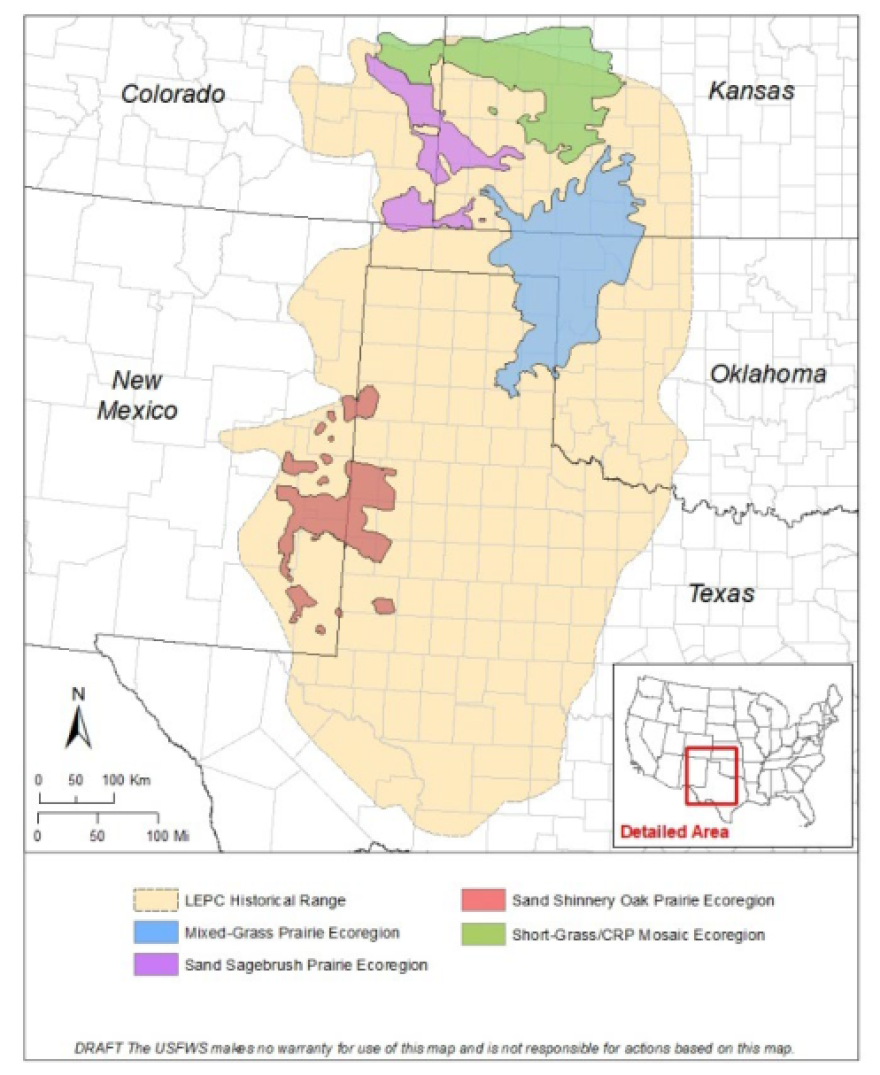

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates millions of lesser prairie chickens may have once scurried across a range of almost 100 million acres across the Great Plains. Today, scientists estimate there are only about 27,000 left in five states – Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico and Colorado. The bird has lost about 90% of its habitat due in part to land development, the spread of invasive trees on prairies, renewable energy projects and oil and gas activity.

Despite its plummeting numbers, the federal government has reversed protections for the species twice, most recently this summer after a court decision.

Now that work will fall to state and individual landowners.

Kurt Kuklinski with the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation said changing rules has made efforts with landowners tougher, even if many want to participate.

“The bird was listed, then delisted, listed again. Now it's being challenged for a second delisting,” Kuklinski said. “That adds greater confusion and uncertainty to landowners. And it creates an atmosphere of maybe distrust is the best word.”

Federal protections are gone, again

After President Donald Trump took office for a second time, U.S. Fish and Wildlife reevaluated its Endangered Species Act rules. It quickly pointed to flaws in the Biden-era ruling in 2022 giving the lesser prairie chicken ESA protections.

Then on Aug. 12, a Texas federal judge ruled in favor of states that had challenged the ESA status of the species. In 2023, Oklahoma and Kansas joined a federal lawsuit – first started by the state of Texas – against the species listing.

It was the second time the bird lost protections. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service previously listed the lesser prairie chicken as threatened in 2014. It was delisted in 2016 following a court ruling, which the agency did not appeal.

The lesser prairie chicken’s most recent ESA protections separated the species geographically with distinct population segments. The southern population is in parts of New Mexico and Texas, while the northern range includes Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado and another part of Texas. Wildlife officials gave the southern population an “endangered” status, while the northern was listed as “threatened.”

Researchers and conservationists say the lesser prairie chicken is an indicator species.

At the George Miksch Sutton Avian Research Center in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, biologist Fumiko Sakoda said the bird’s fate is a reflection of the overall health of an ecosystem.

“If they decline, that is a trend which is something wrong with the habitat,” Sakoda said.

Environmental groups, including the Center for Biological Diversity and the Texas Campaign for the Environment, are appealing the court decision. In the meantime, Kuklinski said the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation is taking part in a multi-state plan to conserve the species.

He said those efforts will largely depend on landowners.

"They're our greatest wildlife conservation partners,” Kuklinski said. “You know, 95% of Oklahoma is private land, and we have very few public land parcels that the government can manage to the benefit of the species, so we rely on our conservation partners who are landowners, private landowners.”

‘A healthy ecosystem for all’

Mark Gardiner’s massive ranch is part of the Lesser Prairie Chicken Landowner Alliance, a recently-formed nonprofit group to benefit ranchers and the bird.

He’s agreed to permanently keep about 14,000 of his acres undeveloped as part of what’s called a conservation banking agreement. In exchange, Gardiner gets paid with money from investors – such as energy companies – that want to offset their impacts.

Gardiner said he was hesitant to sign on at first because the agreement is permanent and strips the ranch of flexibility in certain parts of the land.

But the payments help offset some debt, he said, and his family had no plans to develop the lesser prairie chicken habitat. Plus, he said this conservation helps him meet his own goal: to leave the land better than he found it.

“ Ecosystems and environments are important,” Gardiner said. “Prairie chickens are important, wildlife's important, but people are, too. And so when we can make all those things be healthy, have a healthy ecosystem for all, then we can all go forward together.”

In Oklahoma, landowners have a history of voluntary practices leading to the return of wildlife species, like white-tailed deer and the bald eagle.

"That voluntary approach is really working," said Trey Lam, executive director of the Oklahoma Conservation Commission. "It's worked on other problems that helped solve the Dust Bowl, originally. It helped to put a lot of ground that never should have been farmed back into grass."

The commission doesn't have lesser prairie chicken-specific programs, but other management plans, including red cedar removal and prescribed burns, help the remaining populations. Some of the programs have a cost-share option to cover up to 90% of the financial burden for farmers and ranchers, Lam said. The commission allocates the funds to conservation districts that run the programs locally.

With enough education and mentorship, Lam said there's plenty of incentive and will among Oklahoma landowners to bring the bird's population back.

" But it's going to have to be, really, a public movement similar to what they did to stop the Dust Bowl to get this habitat back to where it needs to be," he said.

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest and Great Plains. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.