The great-great grandson of “Free Frank” McWorter — the first Black man to establish a U.S. town— says the New Philadelphia, Ill., site deserves National Park status to further spread the story of the integrated community, and former slaves migration.

“We say that if New Philadelphia was possible beginning in the 1830s, then maybe (racial equality in) America is possible,'' said Gerald McWorter. “That is the message, and we think that’s important.”

A professor emeritus at University of Illinois, McWorter and his spouse, Kate Williams-McWorter, also a U of I professor, talked with WGLT ahead of their presentation about their book “New Philadelphia,” 6:30 p.m. Wednesday at the Normal Public Library.

They say bipartisan support for such bills in Congress show New Philadelphia’s significance is gaining recognition. During the past year, Illinois' Republican U.S. Rep. Darin LaHood, who represents Central Illinois, and Democratic U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin each introduced bills to make New Philadelphia part of the National Park Service.

Formerly enslaved Frank McWorter registered and platted the town, near Barry, in 1836. He is believed to be the first Black person to do so.

The town stood 20 miles from the Mississippi River and the slave state of Missouri, and at one time was home to dozens who were an active part of the Underground Railroad. Though long abandoned, the town's relevance has stayed alive thanks to the New Philadelphia Association, formed by the town's descendants.

“The great narrative of America is about freedom. And Frank is one of the great stories of freedom — along with Frederick Douglass, along with John Jones in Chicago, along with Nat Turner,” said Gerald McWorter.

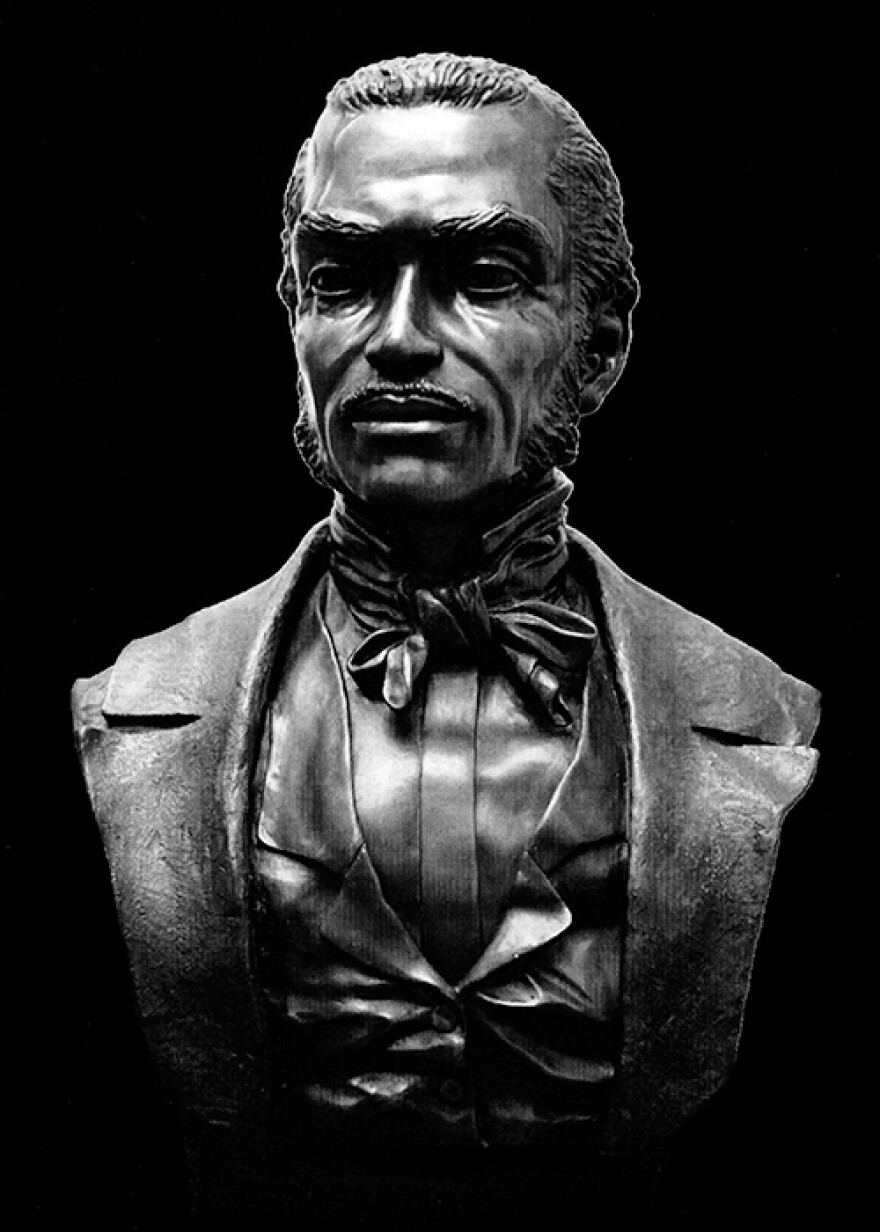

In recent decades, historians have pieced together evidence backing that argument: In 2005, the town was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Since 2009 the 40-acre site has been a National Historic Landmark, and it’s part of the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program. And a bust depicting New Philadelphia founder Frank McWorter stands in the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.

But if the western Illinois spot becomes a formal part of the National Park system, New Philadelphia would gain a global audience, said Williams-McWorter and McWorter.

Family genealogy evolves into nation’s story

McWorter, now nearly 80 years old, has devoted a career to the broad field of African American studies, and he sees that as a direct legacy from Frank McWorter.

“I feel a great responsibility to follow in the footsteps of these ancestors and their commitment to family, their commitment to social justice, their commitment to the possibility of what life could be like,” said McWorter.

At Wednesday’s talk, he’ll explain how shared family stories led to family member dissertations, and his eventual professional endeavor to propel the McWorter story beyond family reunions.

“There’s been a new level of significance, as we have learned how important the story is not just for our family, but for our community and the country,” he said.

Born into slavery in 1777, “Free Frank” was the moniker New Philadelphia’s founder earned when buying not only his own freedom, but eventually that of more than a dozen family members. Before gaining his own freedom, he first used his savings to free his then-pregnant wife, known after as "Free Lucy."

Liberty bled through every aspect of Free Frank’s life, said his great-great grandson: While Free Frank remained enslaved, his eldest son fled slavery, and connected the family with abolitionists in Canada. An entrepreneur, Free Frank saved and traded resources for the Illinois land.

Selling lots in New Philadelphia, he both raised revenue for freeing enslaved relatives, and created an integrated community. Although Frank McWorter died a decade prior to the Civil War, his descendants fought with the Union Army to preserve the nation, said Gerald McWorter.

Most research on New Philadelphia and Free Frank has produced scholarly work centered on the 1800s. But this latest book aims at a general audience, said Williams-McWorter. The book includes hundreds of photos and stories covering two centuries of New Philadelphia history.

That ranges from indigenous people — the Potawatomis in particular, who arrived in Pike County’s Hadley Township prior to Free Frank and other settlers — through today’s New Philadelphia Association working to gain National Park status for the long-abandoned site. It also tells the stories of residents who stayed in the area through the 1950s, including Gerald McWorter’s father.

Tucked between Mark Twain and Abe Lincoln

New Philadelphia occupies a unique space, geographically and structurally, in the discussion of the anti-slavery movement, said McWorter.

In the Midwest, abolition is usually talked about in terms of Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens' pen name) in Hannibal, Mo., to the west, and Abraham Lincoln in Springfield to the east, said McWorter. These major figures played roles in the movement, to be sure, said McWorter. But left out of the discussion are the enslaved and freed Black people who took active roles in the struggle, he said.

“So right in the middle of this highway that runs from Springfield directly to Hannibal is the agency of Free Frank McWorter.” The residents of New Philadelphia, living so near the Mississippi River, and the slave state of Missouri, took active roles in helping escaping slavery. The author says his own family’s oral history long passed down speaks of it:

“It was said that if a freedom seeker got to New Philadelphia, and connected with the McWorter family, three things could happen: One, they could get a pair of shoes. Two, they could get a horse. And three, one of those McWorter boys would help them get on in their voyage to Canada,” said McWorter.

The family stories have found corroboration: Archaeologists discovered two shoe cobblers had been in the village; historical records show “Free Frank” handled the wild horse franchise in the area; and the National Park Service validated correspondence between Frank’s eldest son and abolitionists in Ontario, Canada.

New Philadelphia’s erasure

So, if New Philadelphia was a thriving integrated small town in mid-19th century, what happened?

Among U of I archaeologist Christopher Fennell's studies of the area was one focused on the railroad question. He found it likely that racism tied to pro-slavery business took the town off-track, said the authors.

Williams-McWorter said evidence points to a powerful Missouri consortium building a railroad, which should have had a stop in New Philadelphia, but instead rerouted around the community. It’s not far-fetched that railroad tycoons in Missouri, a slave state, would harbor ill feelings toward a place like New Philadelphia and its vocal abolitionists, she said.

“So it is a bit troubling” to consider what that may have done to the town, said Williams-McWorter.

It lost its post office in the 1880s, though residents lingered there another few decades. Eventually all the structures disappeared too.

Despite its subsiding, efforts by New Philadelphia descendants mean the town’s history is coming back to light. On Sept. 13, the association sponsored “Free Frank Freedom Day” in Pike County. Over the past year, the community’s story has been added to the Chicago Public Schools curriculum.

Exhibits on New Philadelphia are at museums such as The National Museum of American History and closer to home at Peoria Riverfront Museum. Pursuit of National Park status has led to headlines in publications such as The Chicago Tribune and The Washington Post, to name a few.

McWorter sees that as promising. Today’s Black youth, in particular, need to know about the role enslaved people had in forming this nation.

“It is often thought that Black people contributed little to the history of this country. And nothing could be further from the truth,” he said.

"'Free Frank’ McWorter is a model for us to continue the freedom struggle, because the struggle is not over. And that's something that everybody in the Black community should know – most do know. And so Frank becomes a model that creates a possible legacy to that freedom struggle to continue.”

The Urbana authors’ Wednesday book talk will be accessible in person, or virtually. To register, contact the Normal Public Library.