This is the final part of WGLT’s weeklong series The Next Shift about workforce issues in McLean County: The Future.

Bloomington-Normal and the rest of McLean County have a worker shortage. So does much of the rest of the nation. Policymakers and educators are grappling with a multiyear challenge to increase the supply of workers who can keep the area financially strong and vital.

The workforce shortage has been coming for years. In August, there were 97,000 non-farm jobs in the McLean and Dewitt County Labor Market area, according to the Illinois Department of Employment Security (IDES). The Bloomington-Normal Economic Development Council maintains the August number is probably lower than reality because not all Rivian hiring has shown up in data sets.

But that is still several thousand jobs below the size of the labor force in 2013, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the trend had been declining in the decade before the pandemic.

Rivian has been both blamed and praised for the worker shortage. The electric automaker is not the only factor affecting the regional workforce, however, perhaps just the most visible with ever more plentiful numbers of snappy-looking electric trucks and SUVs rolling quietly rolling along Twin City streets, and a massively expanded production facility dominating the northwest side of Normal.

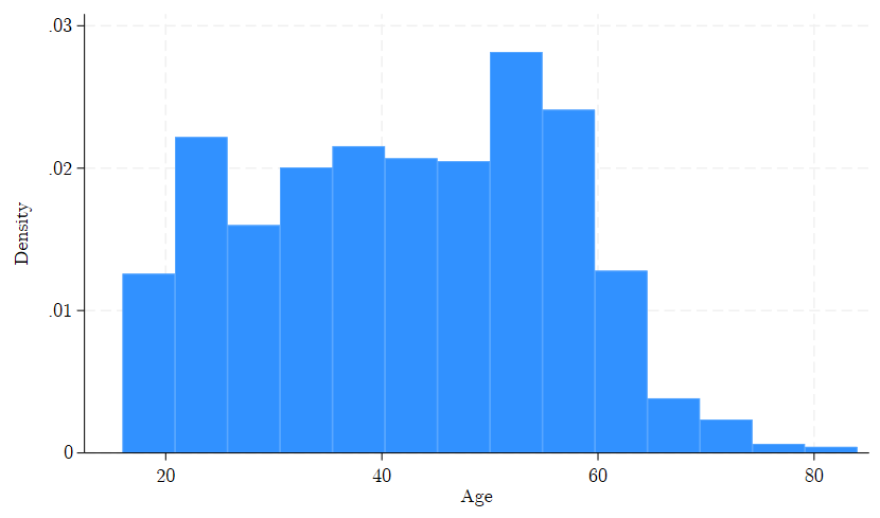

A quieter, but perhaps more significant contributor to workforce challenges has been the retirement of the Baby Boom generation born after World War II.

Goodbye boomers

The Baby Boom generation (1946-1964) already was retiring before the pandemic. In 2016, the size of the Illinois workforce topped 6 million people. Last year, state figures showed the number of people working was 5.9 million, and from 2010 to 2020, revised census figures showed the Illinois population nearly static.

COVID accelerated the retirement trend. Scholars writing for the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis estimated that nationwide “there are 3.3 million or 7% more retirees as of October 2021 than in January 2020.”

The Pew Research Center also estimated retirements in 2020 during the height of the pandemic were 1.2 million more than the average 2 million per year in the years before the pandemic.

There’s general agreement that most of those people will stay retired, though that’s still a little squishy.

“Nonetheless, not all were adequately prepared (financially) for retirement and some of the younger retirees may still re-enter the workforce,” said the Illinois Department of Employment Security Illinois Economic Report 2023, issued in September.

Economist Mike Doherty of Normal agreed. Retirement sometimes doesn’t mean taking retirement.

“First of all, a lot of them are still working. They’re not retiring at 62 or 65. And then even if they are, it’s pretty tough to absorb the housing costs you are seeing,” said Doherty.

The dream of retiring to Florida or Arizona falls to the reality of home prices in, say, Phoenix, he said.

“To a large extent, a lot of baby boomers have been priced out of being able to move out of the area,” said Doherty.

Patrick Hoban, CEO of the Bloomington-Normal Economic Development Council, confirmed data showing Twin City baby boomers do tend to age in place.

Even when they do fully retire, Doherty said they create a lot of economic activity — not only through their own spending, but in lower-paying and volunteer positions with not-for-profit organizations that need community service.

Labor force participation in Illinois remains higher than in the nation, according to the state report. That is the ratio of employment to population.

“Even though the unemployment rate in Illinois is higher than the nation’s unemployment rate, Illinoisans are actively searching for work at a higher rate than the national average; similarly, a greater share of workers living in Illinois are employed than the national average,” said the 2023 Illinois Economic Report.

There’s wide agreement among Bloomington-Normal economy watchers that the Twin Cities is no different from national and state boomer retirement trends.

“A lot of employers that we have been working with, it’s very cognizant on their radar that the current baby boomers are retiring and that’s expected to continue and accelerate,” said Curt Rendall, executive director of program development and innovation at Heartland Community College in Normal.

Rendall’s program works with businesses to fill needs for workers. Generations X, Z, and millennials are smaller groups than the baby boom generation, suggesting the already-pronounced labor shortage will continue.

Workforce needs

"There will be all kinds of jobs open up in trades because that’s where some more of the baby boomers were at. And it’s not going to be so much about just getting any kind of college degree."Shelly Purchis, Careerlink

Heartland Community College works with a labor market analytics firm called Lightcast which finds that, within a 60-mile drive of Bloomington-Normal, all of the colleges and universities can each do a lot more in the health sciences, information technology, and manufacturing fields.

“We actually see a gap of 3,000 certifications a year that’s not being met by the workforce. We could graduate 3,000 more people in applied programs and there would be jobs for them,” said Rendall.

To put that in scale, the Lightcast geographical survey area roughly corresponds to the IDES north-central region the state defined as having 302,000 workers last year. The annual unfilled supply, just in the fields Rendall identified, is about 1%. And since those fields are in high demand, there is cross-region competition for new workers that do emerge from nearby educational institutions.

Earlier this year, the McLean County Chamber of Commerce commissioned an Employer Needs Survey of businesses. Illinois State University's Center for Specialized Professional Support did the study. More than 100 businesses, ranging widely in size, responded. Together, those businesses employ more than 30,000 people, a significant chunk of the Twin City workforce. In all, they expect to add more than 2,500 jobs in the next three years.

Businesses said they will need to add the most jobs in education and training, health sciences, business management, hospitality, and tourism. Manufacturing came in fifth in expected job growth. The labor department defines 16 career clusters that broadly represent the focus of certain jobs. Businesses that responded to the survey also ranked the expected job additions in these career clusters. In rank order, they are business management and administration, marketing, human services, and finance and insurance.

“Apprenticeships are the secret sauce that is the Gen Z and the Millennial whisperer, that this works."Curt Rendall, Heartland Community College

So, there will be more openings across the board — though some areas will have more holes than others. Careerlink is a not-for-profit agency focused on developing the regional workforce. It’s federally funded with a pass-through from the state.

Shelly Purchis, the business services representative for Careerlink, said a lot of the coming vacancies will be blue-collar positions.

“There will be all kinds of jobs [opening] up in trades because that’s where some more of the baby boomers were at. And it’s not going to be so much about just getting any kind of college degree,” said Purchis.

She said a college diploma will still matter, but the nature and marketability of a specific degree might matter more than it used to.

HCC's Rendall said there’s a need to rapidly back fill those areas.

“We see a gap in industries where there was very low turnover for a long period of time. That workforce was trained in the ‘70s and ‘80s and they stayed until now. And a lot of the programs at the colleges and unions kind of shrunk during that period,” said Rendall.

And Hoban of the EDC said he’s not sure even beefed-up training programs will be enough to fill the gap.

“Five years ago, at a conference they had told us in economic development that if you wanted to make money go into auto repair because nobody was going into auto repair and the trades. You are going to be able to charge whatever you want. If you complain about the cost of plumbers now, give it about five or 10 more years when there are no plumbers left,” he said.

Hoban said that training is available now and it’s difficult to fill the slots.

In fact, Federal Reserve Bank economic research shows the wage gap between blue-collar workers and those who have college degrees is shrinking. Some, but not all, of the narrowing is because of inflationary pressure in the last two years and competition for workers in that sector have caused more wage growth at lower income levels.

Workforce training

Businesses, educational institutions, and nonprofits like Careerlink all have a role in filling the need for workers.

Careerlink’s Shelly Purchis works with businesses to fill that need and with individual people to develop their own talent. it can be specific or general training.

“For example, I just had one that put one individual through a CDL program because it would assist them in delivering their product. But then I had another company that has leadership needs and they are putting 10 people through,” she said.

In the last year, there has been a lot of demand for leadership training. It’s a program called "incumbent worker." In the past, companies were likely to bump someone up from the ranks to a position of greater responsibility, but not give them formal training. Now, the workforce shortage and new cultures of working from home have changed the nature of leadership and made retaining and finding new employees more challenging.

Purchis said leadership education is a response.

“They look at leadership as … OK, let’s make a cohesive team and a better working environment to encourage more people to come in and also figure out how to recruit more people, too,” she said.

Requests for leadership training have come from a lot of different Twin City firms, including property management, manufacturers, and some nonprofits. Another reason leadership training programs may be popular, Heartland’s Curt Rendall said, is because societal changes are creating roles that were never there before.

“In these new emerging industries, from electric vehicles to cannabis to data analytics, people that come in on the ground floor today are managers in two years. And then they are moving further up into administration after that,” said Rendall.

The Bloomington-Normal workforce is heavy in the insurance, government, education, manufacturing and agriculture sectors. Rendall said those will continue to be strong.

“Finance, business, and insurance is an incredible opportunity. There are an estimated 133 vacancies per year,” he said.

Heartland’s workforce development center and programs try to build more high-value positions, said Rendall, noting the college worked to build capacity in electric vehicles the last several years. He said a recent meeting of people involved in EV technology shows there is more the college can do.

“Energy storage is going to dwarf anything that we see even with electric vehicles," he said. "Right now, we’re developing the electric vehicle charging infrastructure technician to help build out the national electric vehicle charging infrastructure for the country.”

In health sciences, he said programs already exist. It’s more about growing capacity in those.

Apprenticeships

Heartland, Careerlink, the State of Illinois, unions, and the federal labor department are all pushing for the development of apprenticeship programs as a way to be proactive about filling future job needs.

“The new buzzword is talent pipeline management, that we’re really ensuring there will be people that fit with the company and have the right culture ready to move into those roles,” said Rendall.

And apprenticeships line up directly with what area businesses said they are interested in doing as part of that Chamber of Commerce Employer Needs Survey.

“There is a lot of funding opportunities coming down from the state right now regarding apprenticeships and building apprenticeships,” Amy Julian, director ISU’s Center for Specialized Professional Support, said in July.

The labor department identifies 1,300 occupations that are good for apprenticeships. Rendall and Purchis said almost any of those can mix on-the-job and classroom training. Yet Purchis said those same businesses are not asking for apprenticeships.

"I think one of the things that makes them nervous about it is we talk about it being a longer-term solution and the employers are looking for something quick right now because they are struggling with a shortage of workers,” she said.

According to data developed by Harper College’s model internship program, it takes about eight touch points to establish an internship. Once you do, Rendall said it last and lasts.

“Heartland had an apprenticeship program with Mitsubishi where they trained employees for over 20 years. It was those same employees that were hired back when Rivian opened up that believed in the program and knew how impactful it was, that it was their first order of business to rebuild that apprenticeship,” said Rendall.

Another reason to push apprenticeships involves the peripatetic nature of younger workers. They tend not to stay too long. The average millennial and Gen Z worker person keeps a job for 2.8 years, said Rendall. That’s a huge tax on firms that have to repeatedly search for people, vet them, and onboard them. There’s also an emotional toll from losing colleagues you have just invested in. Apprenticeships can be two to four years, and Rendall said if they stay for another two, the company gets up to six years right off the bat.

“Apprenticeships are the secret sauce that is the Gen Z and the Millennial whisperer, that this works,” said Rendall.

It also helps young people really decide what they want to do. People are hesitant to invest time and scarce resources in training for a career they don’t know will be a good fit. Rendall said by making the match early on, they can choose quickly whether they like it.

Another disconnect in the Chamber survey is between what company hiring agents believe about their culture and loyalty, and what workers see.

"Employers feel that they can convey their meaning and purpose and give advancement. But employees are leaving the community for opportunities elsewhere. So, there's a disconnect," said Sarah Blalock, workforce innovation coordinator at ISU's Center for Specialized Professional Support.

Employees leave town for better pay and other factors all the time. Rendall said apprenticeships address that, too, and tend to keep homegrown people in the community.

“Apprentices feel so much loyalty and belonging and respect for the company that they have been invested in that they stay long beyond the apprenticeships,” said Rendall.

The on-the-job approach also helps companies pass on institutional knowledge from older workers.

Technology change, automation and AI

When the digital revolution really took hold in the 1990s, it changed workplaces in big ways. Productivity soared. Technological shifts are on the cusp of doing the same thing again as usable artificial intelligence trickles in. This will destroy some jobs in Bloomington-Normal and create others.

It’s not easy to tell which. Yet.

EDC director Patrick Hoban said any sector that is repetitive is vulnerable to contraction as AI gets more sophisticated. At least one sector, this could actually be neutral for the state because Illinois has some advantages, he said.

“We do have, comparatively to the rest of the nation, some of the lowest costs for electricity here. And some of the lowest costs for land. So, a lot of people who are looking to come here are for manufacturing through automation. So, I can see us holding steady where we are at,” said Hoban.

Even if automation does hit some sectors and reduce employment, Hoban said it doesn't mean less economic activity in the community.

“Manufacturing-wise, the theory is you bring in automation. You can be more productive, and then you have a higher skilled worker there. Even though it’s eliminating jobs you can produce more, so maybe not eliminating jobs. It depends on what they’re making,” he said.

A case in point, he said, is the new and expanding Ferrero chocolate-making plant in Bloomington. A $214 million addition will create a couple hundred jobs, but Hoban said that’s less than would be needed to run a less automated facility. The existing plant has 350 workers.

Economist Mike Doherty agreed with the general theory that upskilled, higher-paying jobs will offset some potential job losses. There is no guarantee, though, that some of those jobs will need to be in Bloomington-Normal. He noted a previous wave of technology in the auto industry shifted newly-created jobs away from Detroit to Silicon Valley.

Doherty said another big employment sector could be affected once AI really sets into the business world.

“We are an economy that’s little more AI vulnerable than other metro areas mainly because of our insurance company base. I don’t know whether or not AI can take over those jobs, but I would think a lot of those would be pretty vulnerable,” he said.

State Farm declined to talk about the medium-term future and any strategic positioning for AI, but did offer this statement.

“We continue to hire new employees to join State Farm based on business area needs. In fact, since the beginning of the year, we have onboarded 1,180 new associates in Bloomington alone. Employee retention is a top priority and has been for many years. State Farm is fortunate to attract top talent and provides benefits that encourage long and successful careers,” said the company.

Hoban said there also is a big caveat about a different sector.

“The one that we could be concerned about if it gets any closer is autonomous vehicles. Because that’s probably 20% of our labor force when it comes to distribution, nationwide, not here. We’re not really big on distribution even though there are a lot of folks looking at us for it,” he said.

It’s not just mid-tier working-class jobs at risk of destruction from AI. It’s jobs of all kinds. Hoban said even his own economic development field has felt it. Whole committees used to track down economic data. Now it’s a couple button pushes, and fewer staff are needed.

Immigration

Immigration has traditionally contributed to the U.S. labor force.

“And historically, Illinois has been very attractive," said economist Mike Doherty. "During the great boom, the great migration from Mexico, which was between roughly 1995 and 2007, and the Great Recession, which is what killed it off, Illinois was regularly ranked fifth behind the four border states for in-migration directly from Mexico.”

Nations with relatively low birth rates like the U.S. help maintain their workforces through immigration. Both the pandemic and Trump administration policies slowed immigration in the U.S. Research by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco suggests those factors slowed labor force growth, and modestly tightened local labor markets.

The effect can be rapid.

“Reopening of borders in 2022 and easing of immigration policies brought a sizable immigration rebound, which in turn helped alleviate the shortage of workers relative to job vacancies. The foreign-born labor force grew rapidly in 2022, closing the labor force gap created by the pandemic. This analysis suggests that, if the pickup in immigration flows continues, it could further ease overall labor market tightness, albeit by a modest amount,” wrote Evgeniya Duzhak.

The situation in Illinois and in Bloomington-Normal is less clear.

Immigrants go to states where the economy is growing, where wages are higher than their home location and unemployment is low. Doherty said a DCEO report last year showed Illinois labor force needs are "fairly well met" for the present. Even though unemployment rates are low, they are still above the national average.

What to do

Despite immigration, workforce development programs, and the the effects of technology, most predict the labor shortage in Bloomington-Normal and the U.S. will last well into the future. To compete, experts said businesses will have to broaden their vision of who a worker should be.

More than half of job applicants are people who haven’t worked in a given area before, even though they may have overlapping skills. That’s according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that said hiring agents should be more open to getting workers from non-traditional settings if they want to compete.

Shelly Purchis of Careerlink noted the state Department Commerce and Economic Opportunity also preaches this.

“They emphasize to us to make sure that when we’re discussing with employers … rethink what their requirements are for the individuals they are hiring. Like, do you really need this listed there? It’s gonna open up more people applying, more people taking a chance on applying for certain positions,” she said, adding it’s natural for people to resist change. But that won’t be a successful strategy for Twin City businesses.

“The companies that are willing to try something different and maybe take a chance on individuals that are a little bit different are the ones that are really going to grow and benefit from this,” said Purchis.

Embracing change also is a must-do for the next generation of workers. Heartland's Curt Rendall said the EV industry illustrates the kind of worker who will succeed is one who is willing to learn and learn — and learn again.

“Software updates are going out on a daily basis, sometimes an hourly basis. The repair protocol today at 2 p.m. might be different than it was at 11 a.m. this morning. And so every time you go back to the protocol. And you never guess that you know what to do,” he said.

The Employer Needs Survey for the McLean County Chamber of Commerce recommended businesses also do a systematic review of compensation and benefits, both in Illinois and nationally, because the playing field is very broad indeed.

“This is a global economy now. So, are you being competitive?” said Sarah Blalock, workforce innovation coordinator at Illinois State University's Center for Specialized Professional Support.