A big chunk of the counselors and social workers in McLean County just got trained in a rising therapy model that can help people overcome anxiety, depression, and PTSD. It's called Eye Movement and Desensitization and Reprocessing, or EMDR.

McLean County's director of behavioral health coordination, Marita Landreth, said the county spent about $150,000 on the training from the shared sales tax fund to which Bloomington and Normal contribute.

“If you bring up a distressing memory, you sort of activate your nervous system, and then you can use bilateral stimulation, which means eye movement back and forth. It could look like tapping on your shoulders or your knees, taxes the working memory in a way that reduces the intensity and vividness of that memory,” said Kelly Smyth-Dent, founder and CEO of Scaling Up LLC, the training firm the county used.

She said a person’s mind cannot hold the memory and the activity simultaneously for very long. It’s like trying to tap on your head and rub your stomach or jump in a circle and count backwards. Eventually, it dissipates the vivid strength and intensity of the memory or trauma.

“What we're finding from the working memory theory is that the brain and the nervous system can only handle so much taxation at one time. The more taxing you do at the same time, whether that's bringing up a memory, also bilateral stimulation, maybe humming or counting backwards or doing other tasks simultaneously, all at the same time, in the same way that the computer screen if you have too many tabs open, eventually it's just going to start closing out tabs. Your working memory system does the same thing."

It may seem counterintuitive to use eye movements and recalled memory to address trauma. Francine Shapiro created EMDR in the 1980s by happenstance, said Smyth-Dent. Shapiro was dealing with cancer diagnosis and medical trauma. She was walking in a park and thinking about those things and noticed as she was walking her eyes moved back and forth and her distress ebbed.

“Now we know it's not specific to eye movement. It's actually any type of taxation. But most of the research on EMDR is done on that eye movement, because that's what we originally thought was the reason,” said Smyth-Dent.

Most research has been done on PTSD involving intense and vivid trauma. Smyth-Dent said newer work shows EMDR also works on any distressing memory that activates someone’s nervous system, not just trauma. The more intense the memory feels, the faster it works, she said. The source of the distress is typically a negative belief about self that is attached to a memory.

“If you and I are in a car accident together but we have different histories, you might walk away and be like, 'Oh, that was a close call.' I might walk away with panic attacks, even though we had the same traumatic experience. It's based off of my history of other near-death experiences, or other types of experiences that felt similar to that. My nervous system then piles that on top of, I'm unsafe or I'm going to die, and makes those symptoms worse,” said Smyth-Dent.

She said the therapy mode even works when a person may not realize the source of their trauma. She cited a well-known book called “The Body Keeps the Score,” saying the body remembers what the mind doesn’t.

“There's something called free association that we use with EMDR. You might start with a particular memory that is the navigation into the memory network. Then any memory connected to that memory will also be naturally processed during EMDR. So other memories, body sensations, feelings, will pop up during the reprocessing, not only the memory that you started with,” said Smyth-Dent.

Some clients can have significant decreases in symptoms related to anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

Some therapists and social workers in the community already had training and certification in EMDR. Marita Landreth said, though, the 100-seat training marks a big jump for the community. That’s more than a quarter of the 379 clinical social workers and clinical professional counselors licensed in McLean County, according to the Illinois Behavioral Health Workforce Center.

“It should have a pretty significant impact. Trauma is a core part of many different mental illnesses, and McLean County has a wide variety of residents with a variety of experiences,” said Landreth. “An impact, not only for counselors and therapists being able to change what they do and improve their practice, but to also impact the lives of everyone else in McLean County, living, working and getting by.”

The Behavioral Health Coordinating Council recommended enhancing certification in this technique, to develop the local mental health workforce. Landreth said it’s possible there will be more training.

“There was a really positive reception. We filled those 100 seats in less than a week,” said Landreth. “Based on the feedback we've been getting and the continued demand for it, I think it would make a lot of sense for us to offer something like this again next year.”

EMDR is not just a standalone therapy.

Smyth-Dent said therapists usually have multiple intervention tools in their kit, and EMDR complements several of those including cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, and prolonged exposure.

“For example, there's a clinic in the Netherlands that does a ton of research. They do full-day therapy. It's outpatient, but it kind of feels like inpatient. They'll do prolonged exposure in the morning, and then they'll do EMDR in the afternoon … and they're piggybacking off of each other, because they can work really well together if done strategically,” said Smyth-Dent.

She said it’s sometimes surprising how fast clients can see results, sometimes significant changes in a few weeks to a few months. Therapists can use EMDR in creative ways as well, in half to full-day intensive sessions that compress weeks or months of therapy into one or two days.

“That's a unique aspect of this particular intervention that other interventions don't necessarily share,” said Smyth-Dent.

Conditions like depression can be hard to resolve. It can recur. Smyth-Dent said changes from EMDR tend to stick, depending on how much is linked to a memory target. And some issues take longer to process.

“If it's childhood trauma, for example, it's going to be pretty insidious into other relationships and areas of your life. If you're 60 years old and just doing it for the first time and you have all this trauma history, it's going to take a lot longer to get long lasting results, versus if you're a child and you have less history,” Smyth-Dent. “It depends on a variety of factors.”

Once something is processed and a shift happens, though, she said that shift doesn't change.

“That person has it indefinitely. There's not like homework involved. It's not like you have to keep working hard at it. It's very deep, intrinsic, internal,” said Smyth-Dent.

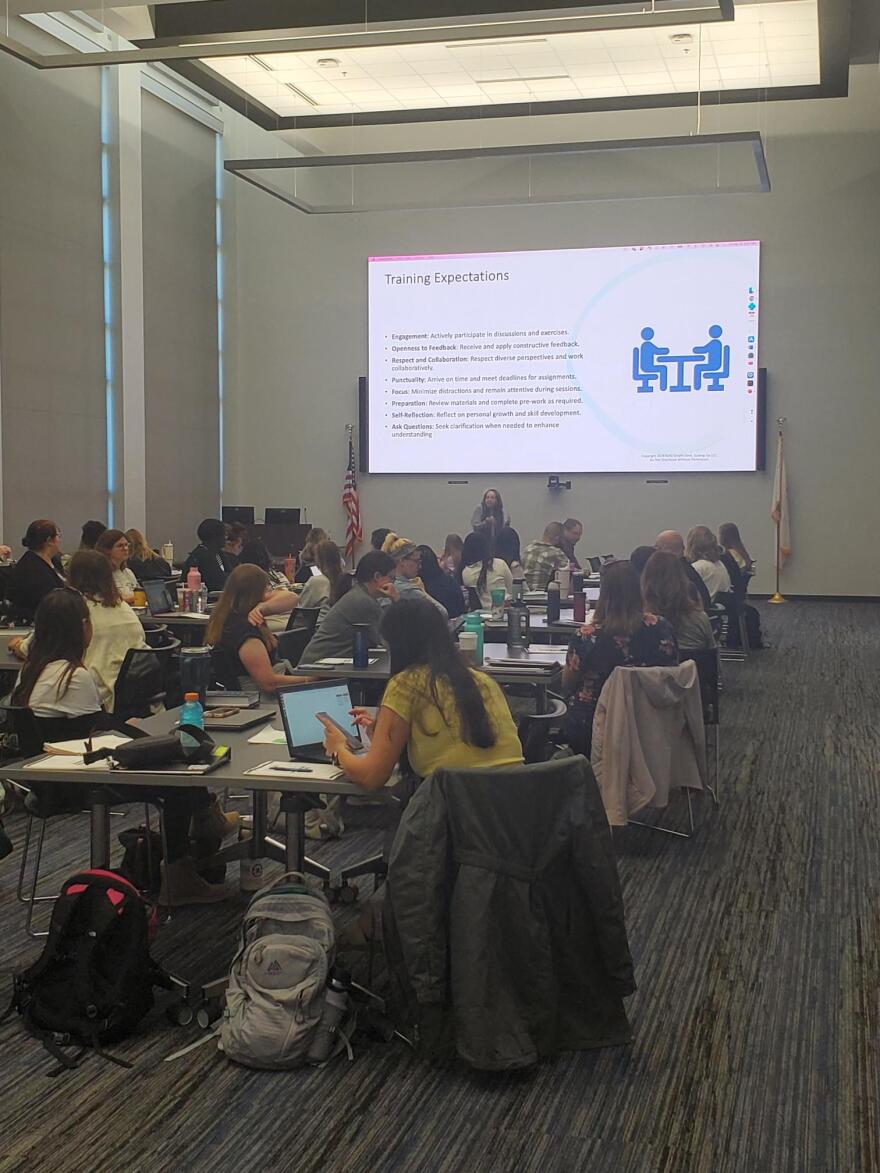

![A picture of two women standing in front of a big display screen. Barbara Sheehan-Zeidler of Scaling UP LLC [left] and Samantha Herrell, McLean County Behavioral Health Coordination [right] start a multi-day training for social workers and therapists in EMDR, held recently at Heartland Community College.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/234e1de/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2144x2196+0+0/resize/880x901!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F9d%2F8e%2Fd08960c240608df0000e0b9aebff%2Femdr-1.jfif)