Just this month, employees at a battery plant in Ohio voted to join the United Auto Workers (UAW) union – an apparent first for an electric vehicle or battery cell plant not owned entirely by the Big Three legacy automakers.

The UAW would very much like Rivian to be next.

The target is ripe. Rivian now has nearly 7,000 workers at its Normal plant in a blue state where voters just constitutionally endorsed the right to organize – and where early organizing already is happening. The plant used to be a UAW shop, back when Mitsubishi built vehicles here.

That doesn’t mean it’ll be easy. Rivian faces enormous pressure from investors and customers to hit production targets and – someday – turn a profit. It has said unionizing would lead to “higher employee costs, operational restrictions and increased risk of disruption to operations,” according to its SEC filings.

Labor experts say a UAW win at Rivian would be a significant turning point in the electric-vehicle revolution that's expected to disrupt auto manufacturing – and auto jobs – on a grand scale.

“That would be a non-trivial increase in its manufacturing base at the UAW, if they were organize (Rivian),” said Marick Masters, a business professor at Wayne State University in Detroit. “And you’d hope this would produce a tipping point in that they could take the success they’ve had there and broaden it to other parts of the auto industry in the U.S.”

Masters said EVs present a challenge for the UAW on three fronts: from foreign-based competition, from U.S.-based legacy automakers that will be transitioning to more EVs, and from new entrants like Tesla and Rivian. Just last week, Stellantis (formerly Chrysler) said it would halt operations at its assembly plant in Belvidere, near Rockford, citing escalating costs to shift to EV production. The UAW said it was “deeply angered” by the move that will impact 1,350 workers.

Another challenge for the UAW is the technology itself.

Generally, the drive train for an EV has a lot fewer parts than a traditional internal-combustion engine, meaning a lot fewer people are needed to make them. And at least for now, battery cell production is concentrated overseas, further decreasing the need for unionized U.S. workers.

“If (the UAW) is unable to get a handle on those things, they’re going to see very quickly their bargaining power dissipate and their attractiveness in the industry diminish,” Masters said.

The UAW’s influence already has shrunk.

Membership peaked 43 years ago and is still concentrated in the legacy automakers, and the union has struggled to make inroads as auto manufacturing has expanded in the southern U.S. Workers at a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tenn., twice rejected forming a union, most recently in 2019.

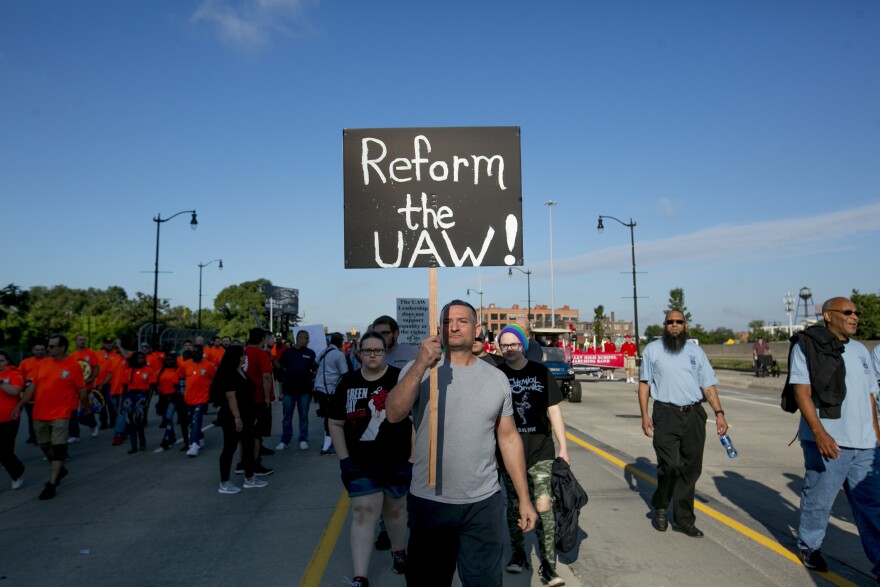

Also tarnishing the UAW’s image is a federal bribery and embezzlement scandal involving former union officials that could lead to a major shakeup in union leadership next month.

Still, early organizing work is underway inside Rivian’s plant, where yellow buttons that say “Union Yes!” are popping up on employee clothing. The UAW has a consultant assigned to the plant, and the union is helping workers bring complaints to the workplace safety agency OSHA – and to the media.

“Corporations like Rivian have an opportunity to show that as we green our economy, we can maintain quality manufacturing jobs, but it starts with a commitment to respect the rights of workers on the shop floor,” Cindy Estrada, vice president of the UAW, told WGLT in a statement.

“Electric vehicles are a crucial solution to climate change and electric vehicle and battery manufacturers are being showered with public money. But what about the workers making the vehicles and the batteries? They are also crucial,” Estrada said. “Despite receiving billions of taxpayer dollars, workers in this industry are struggling. It takes intentional policy to ensure that green jobs are good jobs. That starts by ensuring that auto workers in new assembly and battery plants have the right to freely join together in a union and to collectively bargain with their employers to secure policies like fair scheduling, good pay and retirement, and protocols that keep people safe on the job.”

How to organize

A large share of the auto industry is non-union. One of the biggest challenges the UAW could face at Rivian is employer resistance and getting a fair shot at workers, said Masters.

The UAW has made connections with individual workers at Rivian, helping a few of them go public with safety concerns that could galvanize further support.

Success will require the UAW to “work indigenously” with Rivian’s workers and identify “clusters of individuals” who would be well-connected organizing leaders who can “tip things in your direction and they snowball,” said Masters, the professor from Wayne State.

“It’s a lot easier to manage a team of 10 to 20 than a team of 100 to 150,” he said. “What you want is to get people who are well-connected in the group. They have the right skill set. The good communication skills. Who can speak the language. Who will be immediately credibility when they talk, for their forthrightness and integrity.”

Generally, a next step would be for at least 30% of applicable Rivian workers in Normal to sign cards or a petition asking to be represented. An election would be held, and if a majority of votes are cast in favor of joining the union, it can become the official bargaining unit.

A big unknown is how Rivian will react as organizing takes shape.

On one end of the spectrum, the company could stay neutral or even voluntarily recognize the union if card-signing indicates widespread support among workers, said Masters. Alternatively, the company could hire consultants to orchestrate a full-fledged anti-union campaign to convince workers to vote “no,” using social media, captive-audience meetings, and other tactics.

“The common denominator in companies is that they would like to remain non-union,” Masters said. “Now, the effort they will go to ensure that that happens will vary widely.”

Being 'economically rational'

Where Rivian will land on that spectrum is based more on objective economic incentives rather than the culture or personality of a company, said professor Gordon Lafer, co-director of the Labor Education & Research Center at the University of Oregon. For example, President Biden last year called for bigger tax credits for EVs made in union plants, although that proposal wasn’t included in the final climate bill that passed Congress this summer.

“It’s economically rational for them to say, ‘We want to make as much money as we can for our shareholders, which means we want to pay workers as little as possible, and we don’t want to have to negotiate with our employees. And it’s bad for employees, but it’s good for shareholders. I could say it’s immoral or unethical. But they’re not priests, right? They’re supposed to be making money,” Lafer said.

WGLT asked Rivian founder and CEO RJ Scaringe earlier this year about the prospect of unionization. His response: It’s Rivian leadership’s job to create an “incredible work environment.”

“An environment where it’s clean, well-lit. It’s safe, both physically and psychologically. It invites diversity. It embodies respect. Compensation levels are fair. We have repeatable and predictable work schedules. All those things collectively add up to what it’s like to work here,” Scaringe said. “We hope to always be in the driver’s seat on driving the employee experience. But ultimately, it’s the employees’ choice. Whether they believe we’re doing a good job or not. It’s our responsibility to deliver on that.”

Tesla, the EV pioneer, was notably anti-union. The National Labor Relations Board rebuked Tesla for violating workers’ rights when it told employees they couldn’t wear shirts with pro-union insignia at a factory. None of Tesla’s facilities are represented by labor unions.

Whether Rivian’s Normal plant remains non-union, too, has implications for the greater Bloomington-Normal economy, labor experts say.

“The UAW sees what public policymakers see, which is that auto jobs have been one of the backbones – and in a lot of places, the backbone – of the middle class for almost 100 years. And that’s partly because they’ve been unionized jobs,” said Lafer.

Union jobs tend to pay higher wages. And that’s good news for small businesses in a community that rely on working-class residents having money in their pocket, he said.

“A well-paying, middle-class auto plant is a thing that makes or breaks communities,” Lafer said.