Despite the reputation of Bloomington-Normal as a staid, quiet community with nicknames such as "Borington" and "Insuranceville," the Twin Cities has a long history of protests. While lately there have been a lot of non-violent political protests around Bloomington-Normal, some past actions were not so civil.

1917 streetcar strike

“Bloomington this morning, is practically under martial law, following one of the wildest nights of rioting in its history,” reported the Daily Pantagraph. “Mob attacks street cars power plant and BNN offices. Assaults motor men and conductors.”

Before the New Deal, struggles between capital and labor often happened on the streets of communities.

In the early 1900s, the Bloomington-Normal streetcar system was known as the Bloomington and Normal Railway and Light Company. Often, the owner of a streetcar system also owned the power plant. By the turn of the last century, streetcars relied on electricity and small monopolies developed, said Bill Kemp, librarian at the McLean County Museum of History.

In 1904, a bitter six-month strike of streetcar employees ended in worker defeat. In 1917, streetcar employees had gone three years without a raise.

“They had had enough. The Bloomington-Normal Railway and Light Company gets word of this attempt to organize a union, and everybody is fired. The railway company brings in strike breakers, and they hire detectives to protect their property,” said Kemp.

The workers got no love from the city or the courts that enjoined the workers from distributing literature or demonstrating. On July 5, prominent labor activist Mary Harris Jones, known as ‘Mother Jones,” gave a speech at the Turnverein Hall in Bloomington.

“Mother Jones, it is said, closed her address by telling the men to ‘do something.’ With this incentive, hundreds of men and women gathered in front of the Eagles Hall, apparently waiting for a leader," wrote The Pantagraph. "At the psychological moment, the Park Street's South Main car, in charge of motorman Frank Hart and conductor Grimes, appeared at the south side of the Big Four ... The throng rushed for the car and demanded that the crew leave their electric charge. It is said that motorman Hart drew a gun and made his way from the streetcar to the shanty of the crossing flagman, where he barricaded himself. A number of bricks were thrown at and all windows broken.”

The mob beat the conductor and a detective about the head and shoulders and eventually caught up with motorman Hart sheltering inside the flagman’s shanty.

“Threatening to shoot anyone who approached his point of vantage. A young fellow who was no more than a street urchin … reached through a window and grabbed the gun from Hart's hand. A minute later, he had Hart upon his knees in the doorway of the shanty, begging for mercy, while others who gathered immediately administered a beating by brutally kicking and stoning Hart,” wrote the newspaper.

The crowd then attacked the power plant, armed with "clubs, bricks, coal, and other missiles," breaking many windows.

The mayor of Bloomington refused to meet with the strikers and petitioned the governor for help. The sheriff telegraphed the governor for help, too.

Troop G, 1st Illinois cavalry from Peoria, arrived the next morning and pitched camp near the Powerhouse and at the courthouse square. Several more companies came from Chicago.

Kemp said “1,400 Illinois militiamen set up machine gun emplacements on the courthouse square in downtown Bloomington and at the powerhouse in the warehouse district. It is a show of force. There's also another show of force.”

The largest employer in Bloomington-Normal at the time was the Chicago and Alton Railroad Shops on the city's west side. More than 1,000 skilled and semi-skilled craftsmen marched around the downtown square during their lunch hour.

The C&A employees basically told the City of Bloomington, the street railway, company and their own employer, if the strike does not get settled, they would also walk out. The mayor pleaded with the streetcar company and the two sides reached a contract. Workers got a modest pay raise and small reduction in required hours.

“A union is organized for streetcar motor men and conductors. That union survives today for Connect Transit bus drivers,” said Kemp.

Other protests

In 1970, deaths during an anti-Vietnam War protest at Kent State sparked nationwide student strikes.

At Illinois State University, in what became known as the "flag wars," pro and antiwar demonstrators contested whether the flag on the quad would be lowered to half-staff to mark the birthday of Malcolm X.

In the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan held rallies against immigrants, Catholics, and Blacks in Bloomington-Normal, including one on the land that eventually became State Farm Park. The Klan also marched in downtown Bloomington.

On the other end of the political spectrum, the Communist-Socialist Unemployed Council marched and protested during the Great Depression.

In the summer of 1984, the Normal Town Council passed ordinances limiting mass gatherings and sales of beer by the keg. When students returned to campus, party and alcohol arrests rose dramatically.

The tense town-gown atmosphere sparked protests and on Oct. 3, 1984, one gathering brewed up into something much larger, now known as the infamous "Beer Riot." A crowd of students marched on City Hall, vandalizing phone booths and stop signs as they went. State Police teargassed the crowd, though the wind was in the wrong direction. Both sides de-escalated in the following days.

The 1st Amendment and the sacking of the Bloomington Times

The 1st Amendment right to free expression matters, though sometimes it is not always observed.

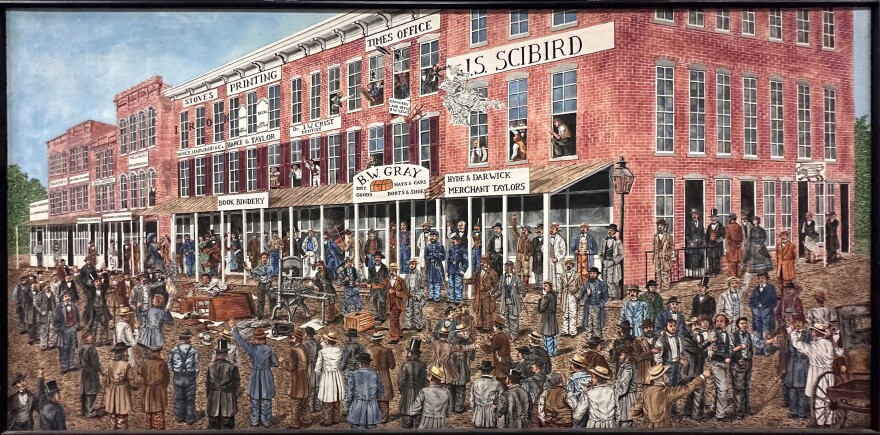

By 1860, The Pantagraph newspaper published both daily and weekly editions. There were two other papers. In those days papers, tended to be organs of political parties. The Pantagraph was the Republican paper, the party of Lincoln. Another was the Illinois Statesman that catered to Democrats and their standard bearer, U.S. Sen. Stephen Douglas.

“The third paper was very interesting, though," said Kemp. "It supported secession and was virulently racist, even for its day. It was known as the Bloomington Times.”

The editors and publishers were the Snow brothers, Benjamin F. and Josiah Snow. Josiah went by Joseph. And provocation was their profession, said Kemp.

“Without the sanction of Congress which is alone empowered to declare war, Abraham Lincoln, the accidental choice of a minority of the American people, giving himself to the extremists of this party has precipitated the northern and southern states into armed hostilities,” The Bloomington Times wrote on June 15, 1861.

The Snows were from Maryland, a slave state. Their publication became so vitriolic, a citizens committee organized by community leaders to address the Snow brothers and ask them to halt publications that gave "aid and comfort to the disaffected and could be tolerated no longer by loyal men."

“This accursed fraternal contest into which Mr. Lincoln has hastened us in contempt of the Constitution he has just sworn to support, is the long-foreseen result of the wicked and persistent assaults made by the party which now holds power in these northern states upon the rights and property of their fellow citizens of the South,” wrote the Times.

Nevertheless, they persisted.

On Aug. 20, 1862, on the courthouse square, the Illinois Volunteer Infantry the 94th known as Old MacLean, was being organized. New enlistees were to go down to Springfield and formally enroll into the war effort.

“Much revelry as one could imagine, a lot of consumption of alcohol. Soldiers are taking an oath to the union. Somebody got the idea to drag the Snow brothers out of their office and have them take an oath,” said Kemp.

The story goes, as the brothers stepped off the platform, one said to the other, something to the effect of, an oath under duress right in front of a mob isn't really an oath to be considered such.

“That was really the what the mob was waiting for,” said Kemp.

The reveling soldiers reviled the Snows as rebels, stormed into the newspaper building on the square, tossed everything in the offices out the windows onto the street and burned it all, from the coal shovel to the printing press.

“We regret it for the damage it has done to the fair fame of our city and county, for the tendency of such deeds to bring our free institutions into disrepute, at home and abroad, and on account of the ill will begot in our hitherto peaceable, orderly, and law-abiding community,” wrote the Illinois Statesman, the Democratic newspaper.

“We have, at all times, exerted whatever influence we possess against all acts of violence, and we very much regret this occurrence in our midst. We do not justify the Messrs. Snow in the manner in which they have conducted their journal. It is not wise to run counter to the sentiments of an entire community unless duty clearly demands it, and there is a fair prospect of accomplishing good by so doing," said the Statesman.

The Statesman was critical of Abraham Lincoln and the administration, but supported the war effort. Kemp said it was a patriotic newspaper that nonetheless supported the Bloomington Times' right to publish without the fear of mob violence and action.

“The McLean County regiment has just been organized for the express purpose of punishing men for their wicked revolt against the government and to force them back again under subjection to its laws. We are all justly proud of our regiment and have formed high expectations of what it shall accomplish in the field. We deem it very unfortunate that before it has left home, some of its members should have been guilty of violating those very laws that they had just solemnly sworn to support and protect against all enemies,” opined the editors of the Statesman.

The paper called for moderation in perilous times instead of adding venom to the "already surging billows of passion" and said if the Snows were really disloyal and showed it through overt acts, the courts were the remedy rather than an illegal punishment.

“The destruction of each other's property, liberties or lives will not make any of us better or more loyal men. Let us all remember that ‘a soft answer turneth away wrath,’ and then ‘if we sow to the winds, we may reap a tempest’,” wrote the Statesman.

Kemp said the Snow brothers were run out of town on a figurative rail. They moved to Paris, Illinois and set up another pro-southern paper. Citizens there chased them away as well. Kemp said the Snows got out of newspapers and spent the rest of the war in St. Louis in real estate.