The Bloomington-Normal Economic Development Council [EDC] and YWCA McLean County are proposing significant public and private sector investment in affordable child care for the community.

After a yearlong study, the report Building McLean County’s Future: A Collaborative Strategy for Childcare Solutions, lays out average child care costs that, coupled with mortgage or rent payments, consumes about half the income of a median household [$78,500] in McLean County.

“There has been a cliff coming for several years. There has been an employee shortage since about 2017 and COVID made that dramatically worse. With the employee shortage, you've seen prices increasing. You've seen providers close. You've seen spots decrease. The whole business model of child care has changed dramatically,” said YWCA CEO Liz German.

She estimated most child care centers in the county operate at less than full staff.

“I have not talked to one single child care provider who has all the staff that they need, which means they're not able to have the full capacity of the center they could have,” said German.

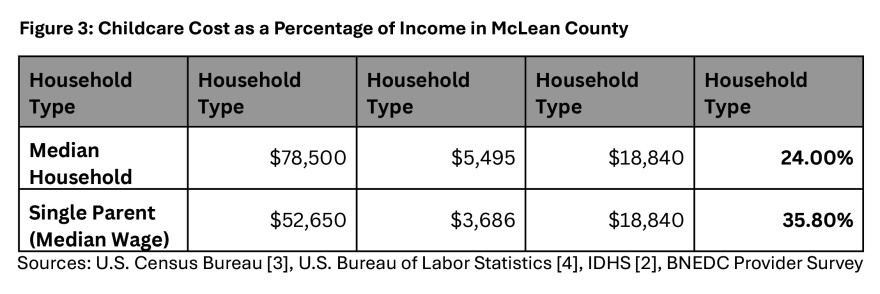

Child care costs alone are about 28% of the median household income and nearly 36% of the median wage of a single parent household in the community. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services affordability guidelines suggest child care should cost no more than 7% of a family’s gross income.

The study involved a survey of child care providers which found the $18,840 average annual child care cost in Bloomington-Normal.

“The typical public-school [college] tuition is less than the cost of child care,” said Nora Harrison, senior community development manager at the Economic Development Council.

Infant care had the highest estimated price at about $1,570 per month last year. Toddler care was $1,325 per month. And monthly preschool costs averaged $1,115. Those costs were significantly higher than the averages in the Springfield, Rockford and Champaign labor markets.

“McLean County's child care costs were the second highest in the state. The only county that was higher than us was Cook County," said Harrison.

Family consequences

The study suggested many families, particularly mothers, compensated for the high costs, by reducing work hours [48%], declining promotions [24%] or leaving the workforce [17%].

“48% of parents reported that child care costs influenced their decision not to have more children,” said the study.

The study also cited Illinois Department of Public Health records showing a pronounced decline in live births in McLean County from more than 2,100 in 2010 to less than 1,700 last year.

“An aging population and declining birthrate increase the urgency of stabilizing the systems that support working families today. Central to that effort is the child care workforce itself, whose availability and stability directly determine whether families can remain in the labor force,” said the study.

Pay

The study found child care worker wages are scarcely higher than for fast food workers and cashiers, and fall behind retail sales positions, customer service jobs and general office clerks, despite significant education and licensing requirements for child care workers.

“Once she heard [the pay], she withdrew her application. We couldn’t compete with her position in the dental office, even with our benefits… The teachers are out there but they too are faced with providing for their families first. The child care model should not be shouldered on their sacrifice,” said one business operator.

Early childhood educator pay also lags far behind school teaching positions, according to the study.

Business effects

The EDC said the situation hinders business growth.

“2022 U.S. Census data indicates approximately 8,500 prime working-age adults in McLean County are not in the labor force, a trend strongly influenced by child care challenges,” said the study.

A business impact study found 57% of responding employers had difficulty hiring or retaining workers because of child care challenges. 65% reported lost productivity over child care issues that included absenteeism, workforce turnover, tardiness, reductions in hours and leaving jobs.

The survey involved businesses that employ more than 20,000 McLean County workers.

Proposals

The EDC and the YWCA suggested expanding state and federal child and dependent care tax credits, caps on reimbursement for care and income limits for child care subsidies. One simple measure, German said, is changing child care subsidy eligibility for certain education programs.

“The apprenticeship programs the state has funded to get people into clean energy jobs and jobs with big companies are not covered by child care assistance programs. People who, in five to eight weeks, could have a full-fledged career with a living gainful wage, sometimes can't take the apprenticeship because they can't get child care,” said German. “It could make a huge difference for those folks.”

The study proposed using an Alabama tax credit program that encourages child care business creation. Illinois does have a tax credit program, though it's not structured the same.

“Alabama's program allows employers to benefit from the tax breaks if they pay for child care. They didn't have to open a child care center. Some employers are hesitant to open a center on site, but they may not be hesitant to help in paying for it. Illinois employers don’t get the same tax benefit that they would in a state like Alabama,” said Harrison.

It suggested using a Michigan initiative that creates regional hubs which administer a Tri-Share program, splitting the cost of child care equally among the family, the state and the employer. That targets affordability for middle-income workers and encourages employer investment in longer term workers.

“If you're an employee… you're motivated to stay there for the time the child is in care, at least the first five years of their life. The longer an employee stays, the more productive they become, the less you have to teach, the less you have to train. They are more efficient at their job. They're able to contribute more to the company. From a business standpoint, retention is the way you want to go,” said Harrison.

That might appear to push the cost onto consumers of whatever businesses in the program produce. Harrison said not really.

“It's already there. When businesses don't have enough workforce to meet their demands, when they're not able to make the production numbers, they're going to raise the cost anyway to meet the bottom line,” said Harrison.

The study laid out a menu of local policy options as well including changes in zoning, grants and special property tax rates to encourage child care business creation. Sales tax relief for child care providers was on the list. Harrison said some of those potential incentives could target the creation of home-based child care businesses. Many of those closed during the pandemic, which not only reduced availability in the system, but impacted workers who have jobs that require nontraditional hours.

“Nursing homes and nurses, those places where they never close. They can't close. Those are the positions that you would want your child in a home setting at those hours,” said Harrison.

Many people rent. Harrison said that is a barrier to business creation.

“Not a lot of landlords are willing to let a home-based child care business operate out of their rental property,” said Harrison.

Offering rental property owners a property tax break could shift that.

“There are opportunities there to incentivize and help create more home care businesses, because they can offer nontraditional schedules as well,” said Harrison.

Universal preschool

The study proposed preschool care for all 3–4-year-olds in schools to decrease parental costs.

“[It] creates a universal, high quality educational foundation for children while alleviating the financial and capacity burdens on the private child care market,” said the study.

German said that proposal could improve the efficiency of the care system because public schools already have some preschool resources.

“One of the conversations we've had with some of the districts are, if you could do preschool for more children and you still needed care, say, from three to five o'clock, that's when a child care provider could step in and help with that coverage and streamline things for everybody,” said German.

German said it’s also possible the state may step in and make that decision for schools anyway, so it’s worth having the discussion at the community level to plan how that could work.

There's a potential disconnect, though, between low wages for child care workers and the need to reduce costs. If early childhood educators who now make a salary similar to office clerks and fast-food workers, improve salaries to a truly professional standard, it will increase costs throughout the system, despite the cost sharing ideas laid out in the report. German said this is a nuanced issue.

“If everybody is able to be working, and employers are spending less on recruitment and turnover and issues, there is a benefit. There's also the kind of intangible prevention benefit of everybody getting to be in child care,” said German.

She said when you put $1 into early childhood, you see $4 to $16 back in the long run.

“We know kids who have been in child care do better. They're more likely to graduate high school, they're more likely to go to college, they're more likely to be productive… The whole system changes. Everything does get better,” said German.

And the caveat, she said, is that the current system is not working. She said if nonprofits can’t stay in the field and the sector is entirely for-profit, there will be consequences including a smaller workforce and less economic activity.

“You will not have frontline workers. You will not have restaurant, retail, CNAs [certified nursing assistants]. So many industries will be impacted. People who maybe don't care about the money aspect as individuals, will care when you go to a nursing home and you don't have anybody to take care of you. You will care when your favorite restaurant is shut down. We just need to look at this from a more holistic view,” said German.

The study called for the creation of a McLean County child care alliance to boost the community’s “economic vitality and long-term stability.”

German said the report is the start of the conversation.

“The data is clear. Child care is not solely a family issue; it is a critical economic priority. Affordability pressures, workforce shortages, and policy barriers are interconnected challenges that no single organization or sector can resolve alone,” said the EDC.

The alliance would seek a few employers to begin a pilot project offering child care benefits to workers, create a community fund for startup grants for five new child care providers, and create a zoning toolkit that could stimulate more home-based child care businesses.