The potential closing of Carlock Elementary School continues to face heavy opposition from residents, business owners and parents of Carlock students.

Although a final recommendation from Cropper GIS, the consultant group that first floated the idea of closing the school, will not come until March, Unit 5 will hold a meeting on Feb. 19 to lay out options for the school district moving forward.

It will be held at 6 p.m. at Parkside Junior High School, the night after the school board's monthly meeting.

Supporters of the school northwest of Bloomington-Normal have formed the organization Keep Carlock Elementary Open to encourage supporters to bring concerns associated with closure to the school board — 23 commenters spoke at the January meeting, with dozens more also attending to support the speakers.

“This parent group is highly organized. They're smart. They do their research. They're finding things with the facts and the figures that don't match up to what we're being told,” said Carlock Mayor Rhonda Baer.

“And everybody who gets up to speak is on point. They knew what they were going to say, and they all touched on something a little different.”

Parent affinity for Carlock Elementary

Supporters of the campaign to keep the school open cite its success as reason to keep it open.

The school was one of three Unit 5 schools to earn exemplary status on the state report card. This means it was in the top 10% of schools statewide, with no under-performing student groups. Proficiencies and growth in math and English were high, earning Carlock the designation for the second straight year.

Still, Carlock has fewer students in high-risk groups, meaning the school had lower expectations to meet than schools with more students fitting categories such as English language learners or students with an Individualized Education Plan [IEP].

Megan and Jerome Hranka both spoke during the January school board meeting. They are parents of two current students and one former Carlock student. They used an attendance exception offered by Unit 5 to enroll their kids at Carlock, despite not living in the town.

The exception allows for applications to enroll at a school other than the one assigned by Unit 5. After learning of the offering, the Hranka parents visited Carlock Elementary.

“We found a school that was welcoming, a well-maintained building with teachers who knew families by name and joyful and confident students,” said Megan Hranka. “This was the learning environment we were looking for.”

Parents of students assigned to Parkside, Fox Creek, Cedar Ridge and Fairview elementary schools are all allowed to apply for an exception to send their children to Carlock. While the school hovers around 100 students, more than two-thirds are bused in from outside communities, including Normal.

Hranka suggested Unit 5 better promote the exceptions to other families in the district to possibly grow Carlock’s student population. She also suggested the policy be rewritten so families do not have to reapply for an exception with each new school year.

A look about town

Carlock has some geographical advantages helping it retain population. One is its location just off of Interstate 74, with several businesses near the Carlock exit. Also near the exit is the school that largely serves district students in the northwest corner of Unit 5.

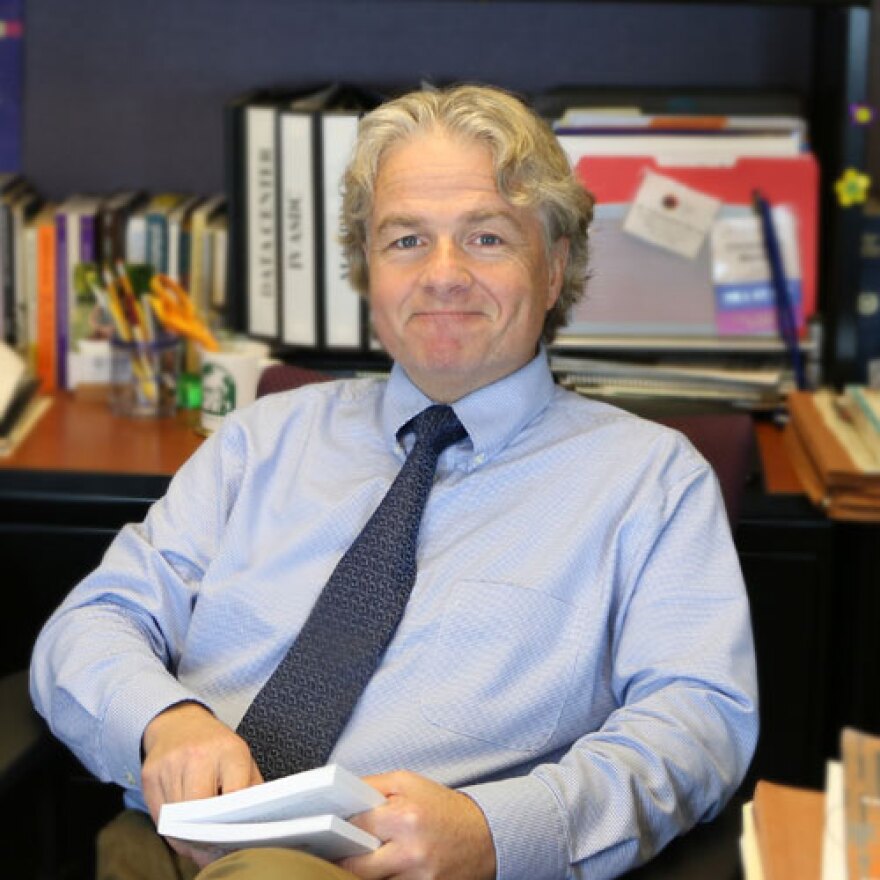

But according to Chris Merrett, director of the Illinois Institute of Rural Affairs at Western Illinois University, that location is still not ideal for Unit 5.

“Looking at where Carlock is located, it's really at the northwest corner of the county, and so it's marginalized, unfortunately. Its geography kind of plays against it,” said Merrett.

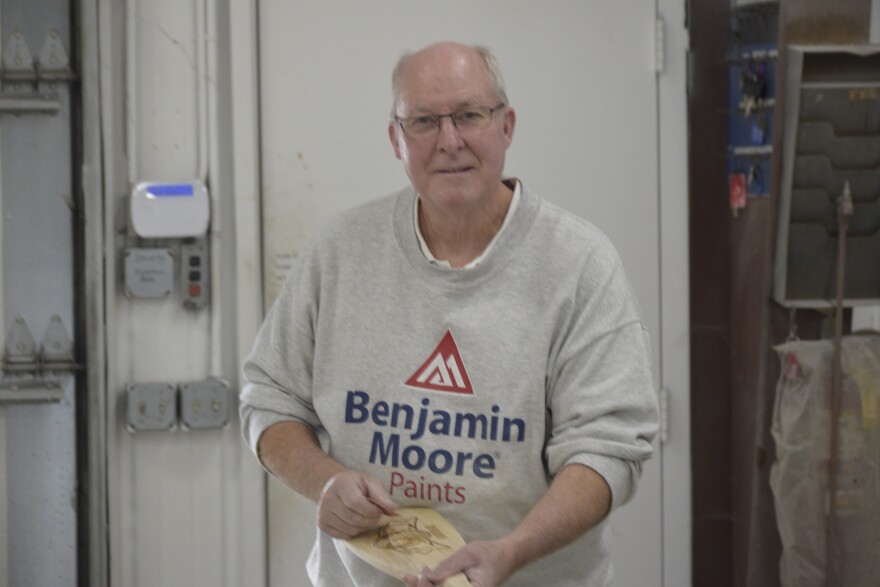

Mike Finley, of Normal, is a retired painter who comes to Piercy Auto Body in Carlock to get personal work done. He previously lived on the outskirts of Carlock, and anticipates businesses will lose customers if people have one less reason to come to town.

“The majority of people probably work out of town anyway. But when their kids are out of town, then you lose that—stop-by after school, pick up the kids, and stop by and get a bite to eat at the restaurant—or, ‘Hey, I'll fill up gas right after I pick up the kids from school,’ so all those businesses miss out on that,” said Finley.

In Finley’s estimation, Piercy Auto Body gets business from people in Carlock, but also from Bloomington-Normal and the surrounding area. He said he would hate to see the school go away because it is a driving factor in many visits to Carlock.

“My feelings are, once you lose it, it’ll be hard to get it back,” said Finley.

Merrett said the loss of a school often begins a population decline in a rural area.

“A school can often be one of the largest, if not the largest, employers in town,” he said. “And so to lose that, you lose car traffic and foot traffic, which then affects things if there are local businesses.”

And with that comes the loss of identity.

“Some families begin to think, ‘Well, maybe we need to move to a different school district.’ And on the flip side, it's also less attractive to bring new people in," he said. "And so when you close a school, it can actually take a community which was already losing population, it can accelerate that downward decline.”

Carlock is growing, bucking the trend the many rural communities. At 548 residents, the 2020 census was the first time dating back to 1960 that Carlock had not grown in population. As of 2023, the population was 560 for the village.

While no other business owners or patrons elected to talk with WGLT, many residents and businesses have signage in support of keeping the grade school open. The signs also are found outside of Carlock, including in the Town of Normal.

Rural declines across Illinois

The tale of a small town losing its school is not a new phenomenon.

Merrett said rural schools, particularly those of the one-room schoolhouse variety, were replaced with larger, more modern schools throughout Illinois by the early 20th century. Eventually, rural schools consolidated with other districts or made other moves to grow the school population, avoiding the issue of being too small to stay open.

But recently, population decline has outpaced efforts to add new people in certain small schools.

“One of the larger issues in many parts of rural Illinois is that population decline. For many counties, their population peaked 20, 30, 40, 50 years ago,” said Merrett. “And the number of people under the age of 20 is, that's sort of the fastest-shrinking cohort in the state of Illinois.”

Consolidation efforts can solve problems in two ways: They put more students in one building and require less staff to teach them than if they were separate. In Carlock’s case, consolidation is not considered an option.

A tale of two subdivisions

A reason for closing the school provided by Matthew Cropper, of Cropper GIS, is the student population is too small for Unit 5 to sustain it. Baer said the community is making efforts to spur population growth, providing a potential solution in the future.

The Stoneman Gardens and Rock Creek subdivisions were added to Carlock in 2006 and 2009, respectively.

The 60-lot Stoneman Gardens subdivision had 40 lots filled when YouthBuild McLean County defaulted on its contract with Carlock. When that happened, before Baer first joined the village board in 2017, the remaining lots were given back to the village to control.

“They sat there for a long time because we just didn't know how we were going to handle that. [We] didn't have a lot of money to do repairs and we didn't know what we were going to do with it,” said Baer. “We don't want to be in the real estate business, we don't want to own all those lots, we want somebody else to own them and build on them."

In 2020, Carlock turned Stoneman Gardens into a Tax Increment Financing [TIF] District. In a TIF, any new taxes generated by increases in property values are spent on redevelopment in that area. The Carlock TIF was then extended along the middle of Carlock up to the Interstate 74 exit, where the village’s commercial district is.

In 2021, a new developer came in and since then, 11 new homes have been added to the village. Baer said this developer recently bought three more lots to build upon.

The Rock Creek subdivision only had seven houses built on its 27-lot space when Mitsubishi announced it was vacating its Bloomington-Normal plant in 2015. Mitsubishi employees living in Carlock, only about a 15-minute drive from the plant, moved out when their jobs left town.

Since Rivian took its place, which added more demand to a market experiencing a housing crisis in McLean County, developers and people looking to build their own homes have built 10 new homes in Rock Creek.

“So in the last four or five years, we've added 21 homes to a town of 250 homes,” said Baer.

A potential second phase of development is on the horizon for Rock Creek. Baer also said landowners from around Carlock may be interested in having their land annexed by the village, which “would equal about 200 acres. That would double the size of Carlock.”